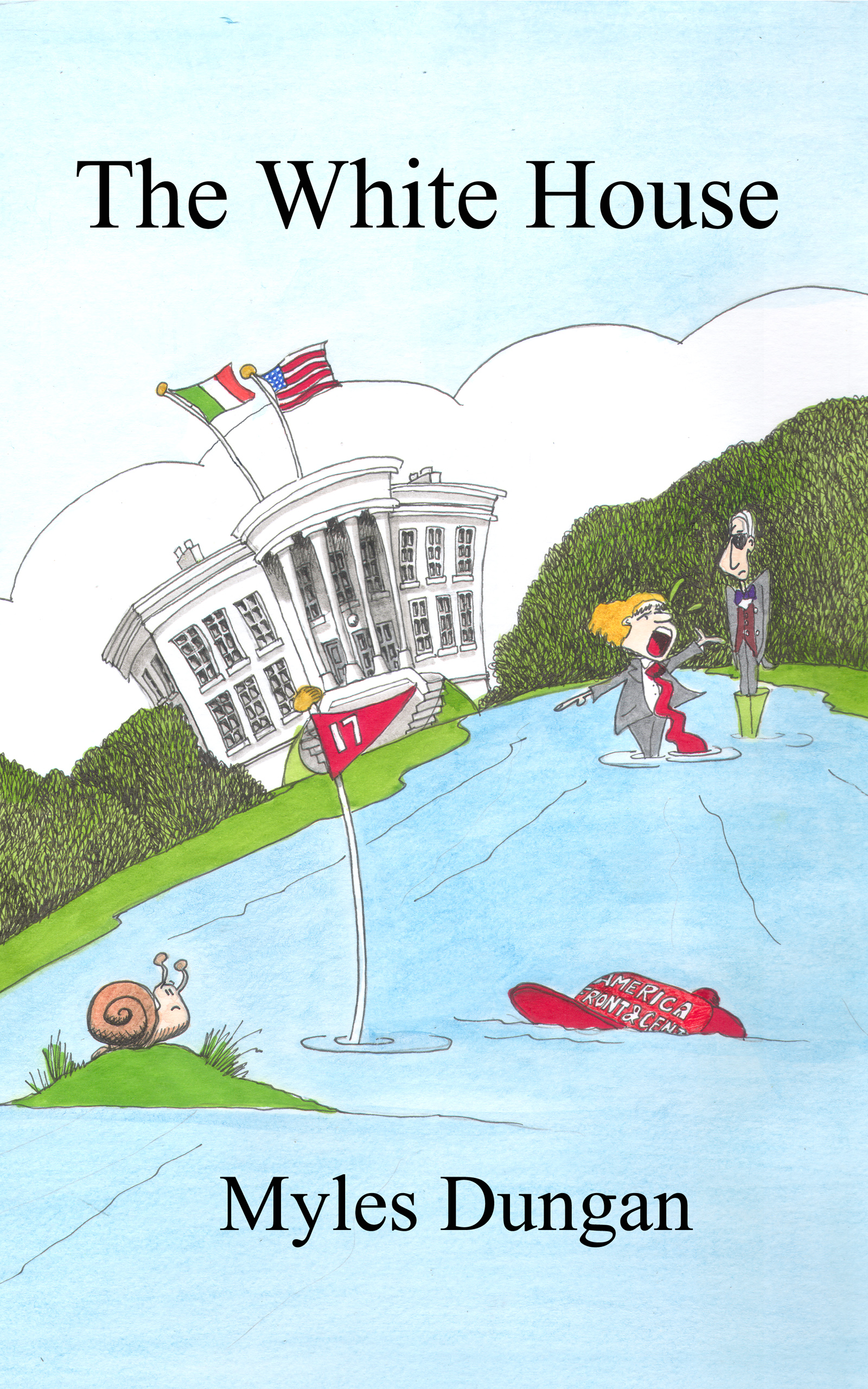

Hardback copies now available. Send me an email (see ‘Contact’)’

Now available on Apple Books, Barnes and Noble, Smashwords and on Kindle

Smashwords coupon code YU78H for a 33% price reduction until 21 May.

U.S. President Tyrone Bentley Trout has a problem. His exclusive Irish golf course is falling victim to climate change and rising sea levels. He wants the Irish to build a wall, and he wants Ireland to pay for it. This is a tale of Russian interference, a tenacious Special Prosecutor, three ex-wives, a frustrated assassin, Ireland’s first female Taoiseach and a climactic golf match.

Here’s a slightly longer preview. Strictly between ourselves. Don’t tell anyone.

PROLOGUE

A future, of sorts, in a barely tangential universe…

The spaniel heard the limo approach and stopped licking his testicles. Fleetingly it occurred to him not to bother giving chase. After all only vassals pursued cars, and he was a feudal Lord. A High King. But the limo was sleek, interminable and enigmatic. Despite the intense cold, and his aristocratic lethargy, the chance to assert his mastery over a chrome and steel Titan was irresistible.

Agamemnon had a rigid modus operandi when it came to chasing cars. Some dogs bark and never leave the kerb. But where was the fun in that? Aggie had an appetite for physical and moral hazard. He really should have been shorting the euro on Wall Street, with his dealer on speed dial.

Agamemnon—his human was a history professor— had inherited his technique from his mother, Athena. Her style was an homage to her own mater, Aphrodite. Both had long since made the journey across the Styx, aged, obese and diabetic, but unmarked by a single car track. So why try and reinvent the hubcap?

As the limo swept past, its black windows impenetrable, splashing brackish water onto the hedgerows of his County Meath domain, Agamemnon sprang into action. He was the Hound of the Baskervilles. He was Cujo. He was Vishnu’s familiar, Death, destroyer of tyres. At least he would be if he ever caught one.

He set off after the vehicle with a surprising turn of speed for an animal who, with a certain physiological inevitability, was tending towards the avoirdupois of his ancestors. His neglected skills quickly reasserted themselves and his enthusiasm for the chase mounted. As the limo approached a pair of imposing gates it slowed down and, to his astonishment, he began to gain ground. Then it stopped altogether. He now held the monstrous beast in thrall. For Agamemnon, the prospect of imminent victory posed a dilemma. He had no idea what to do next. What do you do with an overpowered Leviathan whose body parts were composed entirely of aluminium, rubber, glass, tungsten and PVC?

As Agamemnon pondered his next move, the door opened on the front passenger’s side. A man with a crew cut and designer sunglasses emerged. He began talking aggressively to his sleeve.

‘Hey, dumbass. Why isn’t the gate open? Godammit, POTUS is a sitting duck here.’

Agamemnon became excited at the mention of ducks. Then a rasping voice came from the driver’s seat.

‘Stop with the POTUS, Schmidt. We’re not even supposed to be here.’

‘Sorry sir,’ said the sleeve-talker. He resumed the tête-a-tête with his clothing. ‘Repeat. Golden Eagle is a sitting duck here.’

Agamemnon was puzzled. How could an eagle be a duck, he wondered? He knew he was only a dog, but still, the proposition sounded absurd. Sleevetalker, who clearly had an interest in birds, now approached the entrance and began to press the buttons of a silver pad on the gate’s pillar. After punching the same four keys half a dozen times he reached into an inside pocket, took something out, and pointed it at the pad. He spread his feet a shoulder length apart, extended his arms, and secured his right wrist with his left hand. Then he had second thoughts. He abandoned his awkward stance, reached his left hand into another inside pocket and pulled out a piece of paper. He studied it for a moment, then tried some more buttons. There was an immediate response. A bored voice issued from the metallic grille underneath the buttons.

‘Welcome to Beltra Country Club, how can I help you?’

‘You can open these goddamn gates and get POT … Golden Eagle out of harm’s way, numbnuts.’

Just then the rear window of the limo opened a few inches and a new voice, strident and high-pitched, intervened. To the superstitious dog, it sounded like the whine of the Banshee. An anxious Agamemnon began to whimper and look around for an escape route. ‘What the merry fuck is going on here?’ rat-tat-tatted the Banshee. ‘Is this a negotiation?’

‘Did you hear that, asshole?’ Sleevetalker shouted at the pillar. There was a smooth whirring noise and the gates began to open. The engine of the car started up again. As it did so, Agamemnon feared that his quarry was about to elude him. Before Golden Eagle had time to disappear the black spaniel cocked his leg and urinated on the gleaming hubcap of the limo’s rear wheel. Then the vehicle sped off down what looked to Aggie like an interesting driveway, one with lots of rabbit holes to either side and no obvious badger setts—badgers were trouble. Contented with his lot the little dog strutted back down the country road. He was returning home for another session with a copy of Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France. It belonged to his history professor and, so far, hadn’t been missed. He had already chewed his way through a superior chapter on the gruesome reign of the guillotine and the depredations of Robespierre.

BOOK ONE – THE SEA

‘Cast thy bread upon the waters …’

Ecclesiastes 11:1

That smug patrician, Adrian Breakspear, had plenty to smirk about, thought President Trout. His face must be permanently fixed in one of his lop-sided leers. It was as if he had conjured the waters himself, like some tweedy Anglo-Irish Sea God. This thought, however fanciful, served to increase Trout’s agitation. He imagined Breakspear, a flop-haired Neptune, directing the acquiescent waves of the Irish sea, across the sands of Beltra beach, towards the fescue grass of the ‘White House’ green.

‘There must be some sort of blacklist I can put the bastard on?’ the President mused, staring vacantly out the window of the Oval Office at the bare branches of the crabapple trees in the Rose Garden. They were being pruned by a small army of well-muffled gardeners.

While he doodled on yet another unread daily CIA briefing, Trout couldn’t help feeling that, in spite of everything, Breakspear might ultimately have triumphed. The thought exasperated him. All the more so because the Breakspears, in all their horsey decrepitude, had oozed buttery condescension. They liked to remind everybody that they were descended from the only English Pope. They had seized the Beltra lands by force majeure after their saintly ancestor sent his fellow countrymen to invade Ireland in 1169. In the circumstances, it was hardly surprising that the natives hadn’t taken kindly to the Breakspears. The disdain was entirely mutual and the twain rarely met. An inevitable consequence was centuries of spectacular in-breeding, exemplified by the ubiquity of the famous Breakspear unibrow. While their neighbours were impervious to the Breakspear pheromones, they had a stimulating effect within the extended family. Such a rate of consanguinity meant it was inevitable that a genetic glitch—someone like Adrian— would eventually lose the plot. In fact, he had managed to squander all four thousand acres of it.

Only someone as hapless as a Breakspear, however, Trout pondered with quiet satisfaction, could have fallen foul of pirates in the 21stcentury. Adrian had wagered the entire County Meath estate on a precarious Lloyds syndicate, being spectacularly mismanaged by some of his chinless old Etonian schoolmates. In 2010 the consortium took one punt too many on the insurance of cargo ships sailing off the Horn of Africa. The Breakspears, who had survived the Black Death, Cromwell, the Land League, a plethora of IRAs, and a substantial shareholding in Anglo Irish Bank, finally succumbed to Somali buccaneers with speedy motor boats, garish headbands, and a persuasive arsenal.

Then, from the west, a white knight had galloped to the rescue. Tyrone Trout was a humble New York billionaire hedge fund manager. He had amassed his wealth by failing to lose the entire fortune bequeathed him by his father, and by avoiding tax like most avoid stepping in dog shit. The Fall of the House of Breakspear had coincided with an epidemic of status anxiety on Wall Street. Clifton Cathcart III had begun the stampede of bankers and traders anxious to avoid the social stigma associated with the failure to acquire some heavily encumbered Irish real estate. Warren Buffet’s tide had gone out, and Ireland’s bankers had been caught swimming in the altogether. Wall Street’s Finest were snapping up Irish properties like crocodiles. If the degenerate Cathcart was buying Irish, then so was Tyrone Bentley Trout. The acquisition of the Beltra demesne (‘fabulous sea views, ripe for development’ – Real Estate Alliance) became a sacred mission.

Trout successfully gazumped an attempted purchase by the Irish state, when he offered the Breakspears twice what the Office of Public Works couldn’t afford anyway. This minor coup had added the all-important hint of lemon juice to his mayonnaise. The word ‘public’ offended him, and he had promised his billionaire father on the latter’s death bed that he would never flinch in the fight against briefcase socialism. What clinched his triumph was the ‘sweetheart’ deal he dangled before the Breakspears. The family could remain in situ in Beltra House, while their knight errant doffed his armour and constructed two championship golf courses in the demesne land around them.

Breakspear and Trout had sealed the transaction with a gentlemanly handshake. Unhappily for Breakspear, however, he neglected to count his fingers after pressing the flesh. Had Trout been a man of his word he would have been a mere hedge fund millionaire.

The official photographer who recorded the happy event had difficulty framing his shot. The Anglo-Norman Breakspear was tall and slender, yet to manifest the famous family stoop. The cross-bred Trout was squat. His father and mother had been squat, his younger brother was squatter still. Trout was also a sixty-something, cantankerous, florid alpha male who liked to tell photographers—and most other service providers—how to do their jobs. Trout’s priority was a favourable camera angle, this was essential to avoid drawing unnecessary public attention to the jaw-dropping wig whose very existence he consistently denied.

At first, the deal had worked unexpectedly well for the Breakspears. The discovery of a thriving colony of protected whorl snails on their former estate delayed the start of course construction. After a congenial visit to New York, however, the incumbent Taoiseach, Austin Purcell, had come to see things from the billionaire’s point of view. His considered judgment was that having a ‘signature’ Trout leisure development in Ireland was well worth the inconvenience of flouting the European Union Habitats Directive—at a cost to the state of €20,000 a day. There were unpalatable, and unprovable rumours that Purcell had been well recompensed for his own inconvenience.

Having now accounted for the wildlife, Trout had built his two Jack Nicklaus-designed golf courses—Beltra (Links) and Beltra (Park)—while the Breakspears slumbered. But as soon as the designer’s helicopter had taken to the air at the end of the exhibition match marking the opening of the two courses, the Breakspears had been unceremoniously shunted out. A couple of ostentatious suits of armour were imported for the lobby and their Beltra mansion became a ‘Blue Book’ country house hotel, specialising in upmarket weddings.

After their humiliating eviction, there was one final, despairing throw of the dice from the Breakspears. A shadowy organisation calling itself the New Irish Land League emerged from the snooker room of the Merrion Street Club to fight the eviction. In response, Trout International hired half a dozen sinewy members of the Drogheda Mixed Martial Arts club to act as their champions. Facing a dialogue with six ‘wannabe’ Conor McGregors, the New Irish Land League had discretely ‘called stumps’ and had never been heard of again.

Then, just a few weeks after the disaster of the Presidential victory, came more bad news from Ireland. Nature had chosen to demonstrate its abhorrence of a vacuum, and its support for climate change science, by sending a tempest against his property. The ‘signature’ seventeenth hole of Beltra (Links) had been in the eye of the storm. This was Nicklaus’s personal favourite. He had named it the ‘White House’ in honour of Trout’s maverick run for the Presidency. After an impressive winter storm, all that remained of his verdant ‘White House’ was a partially submerged flagstick. Even this had quickly been claimed by an enterprising souvenir hunter in a kayak. Defying the wishes of the Secret Service, Trout, in the midst of the presidential transition, had gone to have a look for himself. What he saw on his clandestine mission dismayed him. Having started life as a classic dogleg left—with three fairway bunkers in the shape of a shamrock—the ‘White House’ was now an expensive water hazard.

Trout recalled to mind a lesson that his father had once taught him after ‘Junior’ had crashed one of ‘Senior’s’ Mercs. Someone would pay for the damage, and it was not going to be Daddy.

Edward Rothko, United States Commerce Secretary, was a trim, elegant, vigorous looking athlete of early middle age. The former merchant banker was a grizzled, non-smoking, Marlboro’ Man, squeezed into the sharpest of Armani suits. In his previous life, for which he was beginning to yearn already, he had haunted the gym of the New York Athletic Club. His daily 6.00 a.m. workout—always accompanied by two competing personal trainers—was the chisel that had chipped out the angles and shallow recesses of his attenuated face. He liked to think of his body as a temple, though, in truth, it was little more than a modest synagogue. He encouraged both Angelo and Jalen to call him ‘The Beast of the Bourse’ hoping that the nickname would reach the executive washrooms of Wall Street. So far, it hadn’t caught on, and now that he had relocated to DC he would have to start from scratch.

The Presidential Transition Team had plucked him from Price Waterhouse Cooper and deposited him in a swimming pool-sized office on 1401 Constitution Avenue, a few blocks from the White House. Rothko had sat beside a Stanford academic at Trout’s inauguration. She chatted about the charms of eugenics, the elegance of the Bell curve, and her loathing for John Maynard Keynes (‘I’m told he was a compulsive onanist!’), while Rothko shivered in the dry freezing air and wondered what an onanist was. So far he had spent the first three days of his tenure doing little more than conducting job interviews with beetle-browed economists far to the right of the late Milton Friedman while nursing his attendant migraine, and sneaking a nostalgic look at the Hang Seng Index on Bloomberg TV. His tightening hamstrings reminded him of how much he missed Angelo and Jalen.

Today he had been peremptorily summoned to the White House. He had been greeted on his arrival at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue by the carnivorous Buchanan. Trout’s sentinel handed him a (temporary) laminated White House pass.

‘The first of many, I’m sure,’ said the Chief of Staff jovially, in the manner of one of Pavlov’s dogs who has heard a bell ring. The man made Rothko nervous, and it wasn’t just the infamous black eye patch either. The cadaverous Buchanan always looked as if he hadn’t eaten for weeks, and was sizing you up as a potential snack. He had, thought Rothko, the balls of Satan, and the charms of a funnel web spider.

‘Any idea what this is about?’ Rothko inquired, trying not to sound too diffident. He was, after all, tenth in line of succession to the Oval office. He’d looked it up on Wikipedia before agreeing to take the job.

‘It must be about you, I suppose. Just be yourself,’ replied Buchanan unhelpfully. ‘And an occasional display of fawning deference wouldn’t go amiss.’

The laconic Chief of Staff had then ushered Rothko into the Oval office without offering any further enlightenment. As he entered the room the Commerce Secretary detected a musky but vaguely familiar odour. Trout was finishing off what looked like a helping of chicken nuggets. Rothko hadn’t seen a chicken nugget face to face since finishing a teenage internship in a Brooklyn McDonald’s at the insistence of his autocratic father. He immediately understood why the White House Chef had already handed in his notice.

Rothko was motioned by the Falstaffian Trout, his mouth brimming with capon, towards the opposite side of the huge Oval Office Resolute desk. The proffered seat looked extraordinarily like an electric chair with truncated legs. When the Secretary sat, his head barely appeared above the top of the oaken writing table. He was looking almost directly into a carving of a bald eagle with an E Pluribus Unum scroll billowing from its beak.

Without swallowing the remnants of his lunch the President had dived right in, berating his Secretary of Commerce for obscure sins of omission. Rothko did his best to be sycophantic but lacked any bearings. Worse still he became fatally distracted by a sliver of white chicken lodged between the President’s yellowing upper incisors. He studied it attentively as the rant continued, wondering when it would dislodge. Should he say something? What if the President’s next meeting involved lots of hand-holding and congenial grins? Deflected from the message by the medium, he missed the thrust of the President’s diatribe. He gathered that vital American commercial interests in Ireland were at stake, but then became confused by militaristic references to ‘flags’ and ‘bunkers’. His bewilderment had accumulated just enough octane to fuel an interruption when the President curtailed his tirade to swallow a mouthful of something dark and bubbly from a red aluminium can. It had no effect on the sliver of chicken, which still clung to greatness.

‘I’m sorry Mr. President but I wasn’t aware that we had bases in the Republic of Ireland,’ the Secretary ventured. His speech was so rapid that he feared his sudden lack of diffidence might be construed as insubordination. His dental preoccupation also meant that he had no inkling what a military crisis in the North Atlantic had to do with the Commerce Department.

Trout grunted, opened a drawer and produced a toothpick. A tsunami of relief washed over the Commerce Secretary. He was off the orthodontic hook.

‘Who said anything about military bases?’ hissed Trout ‘ We’re discussing an endangered American facility on Irish soil – soil, I might add, which is eroding at an alarming rate and is rearranging the boundaries of a US overseas dependency.’

‘Eh … overseas dependency Mr. President?’

‘Yeh! Like Guam … or Hawaii. US sovereign territory is shrinking by the day and the Commerce Department is doing nothing about it.’

Just then Rothko felt a sharp pain in the meaty part of his right thigh. He jerked upwards. He’d been correct about the chair, he thought. There must be a button under the desk. How many more volts did Trout have at his disposal? The first jolt had only been a warning. Then, looking down, he spied what appeared to be a matted blob of orange marmalade perched on his lap. It had flamboyant whiskers and two malevolent walleyes.

‘Aww,’ murmured Trout affectionately, ‘I see you’ve made friends with Supreme Court.’

‘The Supreme Court, sir?’ Rothko was, by now, so far out to sea that he might have been a minor character in a Patrick O’Brian novel.

‘Not THE Supreme Court, you moron. MY Supreme Court. The cat sitting in your lap. A magnificent specimen, don’t you think?’ purred Trout.

Rothko couldn’t have agreed less, barring the probability that Supreme Court’s magnificence could be measured in litres of pure evil. While Rothko eyed the cat warily, and surreptitiously rubbed his smarting thigh, the President had returned to the matter in hand.

‘You’re my Commerce Secretary, right? Rubenstein … or something like that.’

‘Rothko, sir.’

The President looked at him with sudden interest.

‘Rothko … didn’t my wife—not this one … Number Two … the one with the weird accent—buy some piece of crap painting from you, for my kitchen?’

‘I think you’re mistaken Mr Pres—’

‘You’re right. Maybe it’s the one in the john. Lots of straight lines and boxes.’

‘I think you’ll find …’

‘Doesn’t matter. Moved on already. So you ARE my Commerce secretary …?’

‘Absolutely, sir. However, might I suggest, Mr President, that this may not be within my bailiwick?’ He considered making a joke about waging a trade war but thought better of it. He had already heard rumours about how policy was being made in the Oval Office.

Trout speared a post-it note on his desk with the toothpick. He began to twirl it between thumb and index finger as if it was a square yellow cocktail umbrella.

‘Your … bailiwick?’ he inquired, menacingly. Too late, Rothko remembered that Trout had no grasp of multisyllabic English. He spoke what he called ‘American’, and carved short cuts through language like a Deliveroo cyclist. Rothko took a deep breath and tried again. ‘My province.’ And again. ‘My sphere of responsibility.’ A slight upward movement of Trout’s jowls indicated that he had finally understood. Rothko wondered whether it was the ‘province’ or the ‘sphere’ that had captured the heights.

‘So, who do I need to talk to that can put the shits up the Irish?’ asked the President, stabbing the air with the toothpick, which, to the Secretary’s dismay, had yet to be applied to the purpose for which it was designed.

‘Probably the Secretary of State, Mr President.’

‘State? That scrawny motherfucker. Maybe I should just go straight to the Joint Chiefs of Staff?’

‘That might be a shade provocative, don’t you think, Mr President? I don’t believe Ireland has much of a standing army worth talking about.’

Trout laid the toothpick on the table and opened a second drawer. From this to Rothko’s surprise, he produced a packet of cigarettes and proceeded to light one. Instinctively the Commerce Secretary’s eyes sought out the nearest smoke alarm. Trout intercepted the glance and smirked.

‘They’re all gone. Sprinklers too. Obama got rid of them. Sly bastard.’

Rothko smiled wanly. That explained the strange but oddly familiar aroma, he thought.

‘OK, we’re done here,’ barked Trout. ‘You can go now. Put down Supreme Court and send in Buchanan. Chop chop!’

As Rothko gingerly extracted himself from underneath the ginger tom and beat a welcome retreat, the President suddenly changed his mind and called him back. With a sinking feeling in the pit of his stomach, Rothko returned to the huge oaken desk, by now denuded of everything other than a phone, a hideously mutilated post-it note, and a leaf of discarded iceberg lettuce from the President’s chicken nuggets that had been pressed into service as an ashtray.

Rothko knew instinctively that he was about to be fired. Angelo and Jalen beckoned. He wondered what the previous record was for the shortest tenure as Commerce Secretary.

‘I remember now’, said Trout. In his head, Rothko was already composing his resignation letter. Abrupt or apologia? Terse and enigmatic, he decided. Mostly verbs.

‘It was the john,’ said Trout, thoroughly pleased with himself.

‘Eh … what was, sir?’

‘Where I hung that painting of yours. The reason I remember is that bar a couple of random lines of beige, it was the colour of shit.’

With a flourish, he extracted the sliver of chicken with the nail of his index finger, studied it for a moment, returned it to his mouth, and swallowed it.

As the last shard of Presidential nugget slipped down the Commander in Chief’s throat he turned his attention, once again, to the man he took to be an abstract expressionist.

‘Do you play golf?’ he asked.

You must be logged in to post a comment.