There used to be an expression ‘it’s money in the bank’ but in the wake of the fiscal, financial and credit crises of 2008 we don’t use redundant and inaccurate phraseology like that anymore. That axiom that has gone the way of ‘it’s as safe as houses’ or ‘I’m a markets trader, trust me’. Today we think more in terms of

‘It’s money under the mattress’ or ‘It’s as safe … as this large amount of cash I’m carrying around in my pocket because the interest rate is higher on my backside than with an investment account’ .

Where did it all go wrong? Well maybe it started, in this country at least, in 1797, when the Bank of Ireland took an unprecedented step. In those days cash was King, and cash was gold, or silver. No gold, no goods, unless you were a member of the 10,000 or so landed aristocratic families who were allowedto run up debts. But you still had to settle those with gold at some point … didn’t you?

Anyway. It’s the end of the 18th century and, as usual, Britain is at war. Which is really to say that England is at war and everybody else is expected to chip in and help pay for it. In this case the opposition was provided, pretty much as usual – or comme d’habitude – by France. Where would England have been without France? Clearly, at war with somebody else.

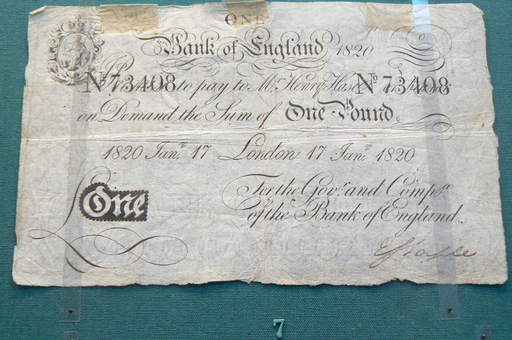

What the British government required above all to conduct its war with Napoleon, was gold. There wasn’t enough to go around. There certainly wasn’t enough in the vaults of the Bank of England to be sending any of it over to the Irish. So, in 1797, the Bank of Ireland was obliged to stop issuing gold it didn’t have and rely on banknotes – already well established at that time – to keep money in circulation.

A few weeks later the stance taken by the Bank was approved of by Irish legislators in the Irish Parliament. Anyone starting to get a feeling of déjà vu here?

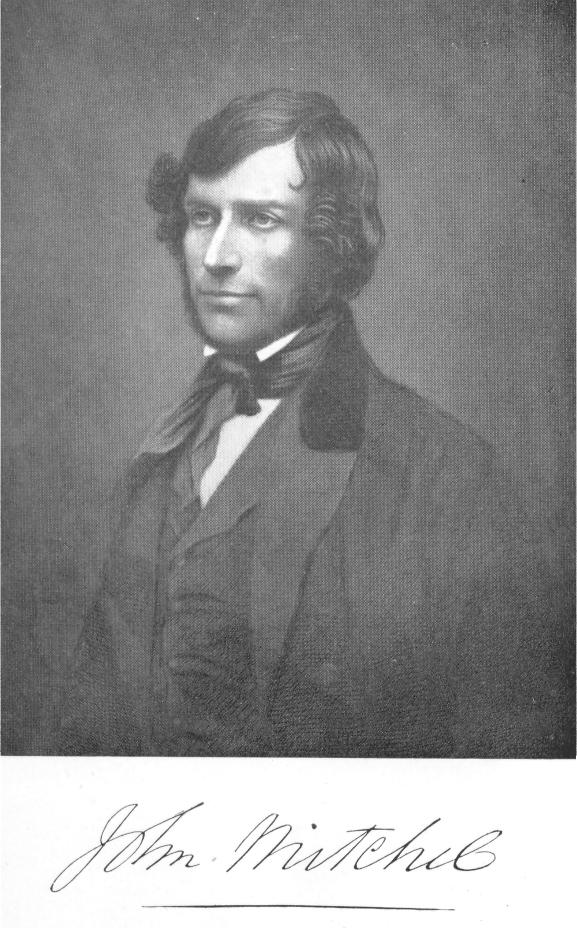

One of the noticeable patterns prior to the withdrawal of gold and the increased issuing of notes in its stead was the establishment in Ireland of a number of private banks who were allowed to issue their own notes. In 1799 there were eleven. In 1803, the year Robert Emmet was hanged, drawn and quartered for the sake of the economy, this number had increased to forty-one. That’s not forty-one branches mind you, that’s forty-one banks! Many of these subsequently went bust and destroyed the lives of their customers. In those days the partners who ran those financial institutions were identified on the banknotes they issued. This meant their clients could see the names, but unfortunately not the addresses, of the men who had screwed them when they went into liquidation.

Perhaps we should thank the Bank of Ireland for the fact that we are no longer weighed down with gold whenever we go to the supermarket or the pub. Their action in withdrawing the precious metal from circulation was certainly to the benefit of men’s clothing. Pockets are no longer subjected to excessive strain. Jackets are not weighed down by heavy metal, except in the case of men who wander around carrying Motorhead CDs. But, as we don’t have much to thank our banks about these days, let’s not bother.

The Bank of Ireland relieved itself of the necessity to issue payment in gold two hundred and nineteen years ago, on this day.

You must be logged in to post a comment.