(Another piece that didn’t make it into the finished work)

The ’satrapy’ of Clifford Lloyd.

‘When constabulary duty’s to the done (to be done)A policeman’s lot is not a happy one (happy one)’(W.S. Gilbert, The Pirates of Penzance)

‘As in the Indian Mutiny the officers of Sepoy regiments refused to believe in the treachery of those among whom they had passed their lives, and remained at their posts until shot down in their mess-rooms, so the gentry in Ireland who remained in the country were loath to believe individually that their doom had been decreed, and that the executioners were to be found among their own tenants’. [1](Clifford Lloyd, Ireland Under the Land League)

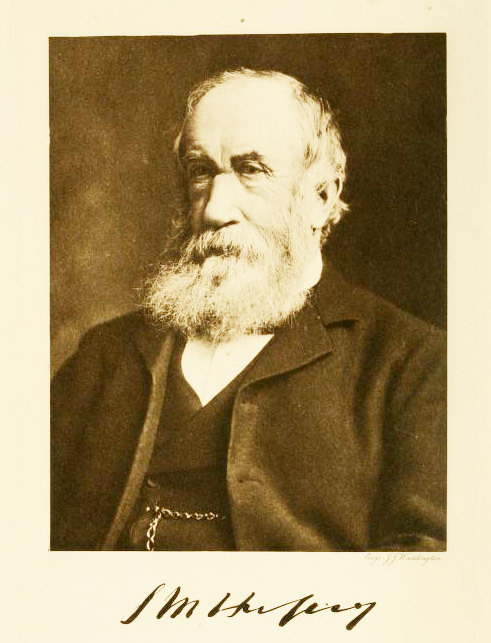

Clifford Lloyd

Another significant Land War memoirist did not dawdle for as long as Samuel Hussey before pouring out his spleen in print. Within a decade of his departure from Ireland, Special Resident Magistrate (SRM) Clifford Lloyd had recorded his impressions of a Land War in which he had played a pivotal policing role. His writing was as robust as his policing. Since he was far removed from Ireland when his volume was published—it actually came out after he died— he had no need to censor himself. Nor did he. He reserved his most cantankerous brickbats for the Land League and the Irish Republican Brotherhood, but he was under no illusions about the nature of the police force upon which he relied heavily during his decade-long tenure in Ireland. ‘The Royal Irish Constabulary,’ he wrote, ‘can best be described as an army of occupation, upon which is imposed the performance of certain civil duties’. [2] Michael Collins could not have put it more pithily. The fundamental difference between these two warriors was that Lloyd had no problem whatsoever with the idea of an occupied Ireland whose elite was being protected by a 12,000 strong paramilitary force with associated surveillance and intelligence duties. A force that shifted itself, now and again, to such unrelated banalities as closing down public houses for entertaining customers after hours, or investigating the occasional burglary. Lloyd, born in Portsmouth in 1844, graduated from Sandhurst, worked for the Burmese police for a decade, and was called to the bar in 1875, a year after being appointed a Resident Magistrate in Ireland. It was in that role that he appears to have found his true calling in life. The avocation of Irish Resident Magistrate has been entertainingly romanticised in the three ‘Irish RM’ books of Somerville and Ross (aka Edith Somerville and Violet Florence Martin) in which Major Sinclair Yeates moves from England to take up such a position, a magistracy being ‘not an easy thing to come by nowadays’.[3] While the three books of the adventures of Major Yeates are not entirely apolitical (one of the stories in The Irish RM and his Experiences is entitled ‘The Whiteboys’), the narrative is largely one of japes and jiggery-pokery, laced with dollops of cultural cringe—Yeates is slow to adapt to rural Ireland—rather than the humourless realities of such an avocation in the late nineteenth century.

During the First Land War there were 72 resident magistrates in Ireland. They were not required to have any awe-inspiring qualifications (Lloyd was one of the few with a legal background) and ‘many gentlemen obtained these appointments, not on account of their capacity, intelligence or experience, but as a reward for political services rendered to the government of the time by those who supported the candidates’ applications.’ RMs tended to be drawn from the ranks of the RIC, the Colonial Service, or the military. Before the onset of the Land War duties were relatively light—this was reflected in a salary of between £425 and £675 in the 1870s— and usually of a judicial nature, although RMs also had some responsibility for public order and for keeping the Castle informed of criminal and political developments in their bailiwicks.

Lloyd, however, was no run-of-the-mill RM. He was an über-magistrate, who, along with four other appointees, became an elite Special Resident Magistrate (SRM) in early 1882. Initially these five trouble-shooters were to be called ‘commissioners’, but that idea was dropped after objections to such nomenclature by Crown lawyers in Dublin Castle, some of whom were opposed to the creation of these enhanced portfolios in the first place. Lloyd, whose experience had been as an ordinary resident magistrate in Down and Longford, was allocated Clare, Limerick and Galway as his sphere of operations. The other four were appointed to Kerry, Cork, King’s and Queen’s Counties (Offaly and Laois), Leitrim, Westmeath, Roscommon, Waterford and Tipperary, counties where ‘outrage’ had become a way of life. The creation of the new SRM role was an attempt by W.E. Forster, the beleaguered chief secretary, to come to grips with the radically changed role of the RIC. As Lloyd put it himself: ‘The police were harassed to the last degree … their legitimate work had become quite neglected. They procured little or no information, and murders were of frequent occurrence, while it can hardly be said that any serious effort was being made in detecting criminals’. Hence the reliance placed on the quasi-military supervisors of five sub-districts to monitor security in their area and take responsibility for co-ordinating the activities of the police (12,000) and military (30,000) when it came to curtailing and punishing the perpetrators of agrarian violence and protecting the obvious targets of ‘moonlighters’.

In his brief foray as an SRM Lloyd succeeded in becoming persona non grata #1 with the Land League leadership, Irish Party MPs, tenant agitators west of the River Shannon, and United Ireland. He managed to conjure up a formidable array of enemies, while retaining the loyalty of Forster for his insistence on ‘the law being obeyed and order preserved’.

His first claim to notoriety came shortly after his transfer from Longford to Limerick in May 1881. His earliest test came in the environs of Kilmallock and Kilfinane, rich dairy country with relatively few indigent tenants. Here the roost was ruled by the famous ‘Land League priest’, Father Eugene Sheehy, president of the Kilmallock branch of the Land League. Lloyd’s assessment of the status quo in the area was terse. ‘In this district there had been no murders, for landlords and agents alike had been driven away, and even those loyally disposed among the people prudently bowed to the authority of the Land League in preference to being shot for opposing it … I found myself face to face with a state of affairs recognised to be bordering on civil war’. Lloyd did not temporise. Within a fortnight of his arrival, he had despatched to jail Sheehy and most of the committee members of the troublesome Kilmallock and Kilfinane Land League branches (‘the hostile power in occupation’). Sheehy thus became the first priest to be arrested during the Land War and his incarceration became both a cause célèbre and a warning to other militants that Lloyd meant business. Lloyd supervised the arrest of Sheehy personally. An attempt was made by the RIC to roust the priest out at 5.30 a.m., but he declined to put in an appearance until 7.00. By this time the street outside his house was ‘already thronged with an excited crowd of people’. Lloyd anticipated bloodshed. Instead, Sheehy, as he was led away peacefully, was treated to displays of extreme deference. ‘The people fell upon their knees as he passed, and seized his hands and the skirts of his clothes, while begging his blessing before he left them. Shouts of defiance and awful loud curses greeted my appearance as I walked towards the barracks through the people.[4]After the release of the Kilmallock and Kilfinane ‘suspects’ in the autumn of 1881, Sheehy did not let up in his invective against Lloyd. In her ‘war diary’ of the tenure of her father as chief secretary, Florence Arnold-Forster, an admirer of the Clare SRM (‘I cannot help having a strong feeling for Mr. Clifford Lloyd’) recorded Sheehy, in an entry of 30 September 1881, as ‘foaming at the mouth in personal abuse of Mr. Clifford Lloyd, whom he described as being like Richard III in mind and body.’ The reference to the last Plantagenet King was because of ‘some rheumatic stiffness in Mr. Clifford Lloyd’s neck which gives him rather a high-shouldered look’. The chief secretary’s daughter, however, asserted boldly that Lloyd ‘has the mastery of Kilmallock’.[5] In deriding his physical appearance United Ireland was less oblique than Sheehy, referring to Lloyd as ‘the hunchback’. [6]

William O’Brien’s newspaper waged a war of attrition against Lloyd long before he painted a target on his own back by becoming one of the country’s first Special Resident Magistrates. In its debut edition, United Ireland was already describing Lloyd as a ‘tyrant’. Later he would mature into a ‘satrap’. While Lloyd would obviously have rejected such categorisations, he would have viewed the hostility of United Ireland as a badge of honour. United Ireland itself does not merit a single mention in Lloyd’s memoir of the Land War, although we cannot be certain whether that is a subtle gesture of contempt, or an indication of painful memories best forgotten.

Lloyd, as one might expect, faced constant threats against his life as he went about his work. In his memoir of the Land War he recorded the receipt of dozens of death threats after the committal to prison of Father Eugene Sheehy and his Kilmallock allies: ‘From this time I was closely watched by policemen. A man slept at my door, even in the barrack; a sentry was under my window by day and night; if I went into the street, there were always in plain clothes two men close behind me, others at a little distance off, before, behind me, and on the other side of the street; if I went for a walk to get a little fresh air, even after a hard day’s work, 10 men with loaded rifles followed me; if I rode, a mounted escort was with me; and if I drove, ten men followed me on cars.’[7]

Naturally, moving around the countryside accompanied by such a retinue was represented by Irish parliamentarians as ‘a passion for theatrical display’. In the House of Commons in August 1882 IPP MP Thomas Sexton accused Lloyd of having been ‘appointed to play the part of despot’ and of travelling around Clare and Limerick ‘amidst the glittering of spurs and the clattering of sabres’.[8] Six months previously a notice posted in Tulla, Co. Clare had offered a ‘£10,000 reward for the corpse of Clifford Lloyd’.[9] No specific reward was offered for the body of Lloyd’s brother, Wilford, an officer of the Royal Horse Artillery, seconded to Clare as a temporary magistrate, but in February 1882 six shots were fired at him as he rode towards Tulla. One of the bullets struck home and severely wounded a policeman accompanying Wilford Lloyd.[10]

The physical and mental strain on Lloyd was clear to Florence Arnold-Forster when she met the SRM in Cruise’s Hotel in Limerick in January 1882. ‘He looked ill,’ she wrote in her diary on 7 January, ‘which is not surprising.’[11] Unlike many of his peers Lloyd tended to be proactive rather than reactive. This served to increase his unpopularity. His attitude towards public Land League assemblies and the provision of huts for evicted tenants were two cases in point. Lloyd never saw a Land League or Irish National League meeting that he approved of: ‘The violent, disorderly, and seditious public meetings of the Land League were palpably illegal, and were followed by crime, bloodshed, and anarchy …. [12]Like his colleagues in the magistracy, Lloyd was under government orders, however, not to prohibit bona fidegatherings. As he might have done with Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy, however, he did not believe such a phenomenon existed as a Land League meeting summoned for peaceful purposes. In a letter to the successor of the ill-fated under-secretary Thomas H. Burke, Sir Robert Hamilton, he was unambiguous in his rejection of the notion of public gatherings for ‘political’ purposes, asserting that ‘they mark the cessation of all true freedom in the districts in which they are held and in which the local ‘Leaguers’ are raised to the position of dictators’.[13]All Land League meetings, in Lloyd’s book, had a subversive intent and were inimical to the maintenance of public order. Whenever feasible, he ignored the political exigencies that dictated Dublin Castle’s approach to public gatherings and proclaimed as many as possible. Before his premature death in 1891, he waxed nostalgic in his memoir about the legal process relating to the right of assembly which he subsequently encountered in the colonial service in India. There, the officer in charge of a district, the equivalent of the Irish Special Resident Magistrates of the Land War era, was solely responsible for public order. ‘Had such a system been in force in Ireland,’ he wrote, ‘we should not have had to deplore a long succession of civil disorders and abortive revolutions’.[14]

In the case of the installation of huts by the League, and later by the Ladies Land League, Lloyd was equally chary. These small huts were intended to house temporarily families that had been subjected to eviction and who had not been readmitted as caretakers on their land. While this facility had a clear charitable intent, there is no doubt that the huts could also be used for a nefarious purpose. They were often erected close to the ‘evicted’ farm in order to maintain around the clock surveillance and ensure that no ‘land grabber’ occupied the farm from which the hut dwellers had just been turned out. In the case of a number of evicted tenants in the troublesome district of Tulla, Lloyd chose to believe that intimidation lay behind the construction of a number of huts in the disturbed district. In the House of Commons on 18 April 1882, IPP MP Thomas Sexton rose to inform the Irish attorney general, W.M. Johnson, in the unlikely event that he was unaware of the development, that: ‘Mr. Clifford Lloyd interfered to-day, stating that the building of the huts was illegal, and ordered the builder to leave the place this evening, and informed him that unless he left he would be arrested’. Sexton wanted to know if this was government policy or a particular quirk of Lloyd’s. He got no satisfaction from the attorney general, whose response was supportive of any course of action the SRM deemed it wise to pursue. Lloyd’s cause was not helped by the fact that one of the evicted Tulla tenants, John Canny, died shortly after losing his farm. An attempt by Irish MPs to highlight this tragedy received short shrift from the administration. It was pointed out in the House of Commons that Canny was not one of the tenants denied access to the huts of the Ladies Land League, and that he was seventy-four years of age and in bad health before his death.[15]

Although Lloyd was better known for the prevention and prosecution of public order offences—he proved adept, for example, at securing the services of platoons of soldiers from reluctant military commanders—than for the red-handed apprehension of ribbonmen and moonlighters, this was largely because his tenure in Ireland coincided with coercion legislation that allowed the authorities to imprison those suspected of committing ‘outrages’. This could be done almost summarily, without resort to the traditional method of disposing of malefactors: trial by jury. Although he unquestionably benefited from this practice when it came to covert ‘ribbon’ activity, Lloyd was not greatly enamoured of the frequent employment by the RIC of the ‘internment without trial’ provisions of the Protection of Person and Property Act. He considered the ‘lifting’ and subsequent incarceration of suspects to be lazy policing. His preference was for the procurement of evidence usable in a court of law. That said, he was well aware that RIC investigators were frequently forced to adopt such a strategy because of the difficulty of obtaining convictions in trials involving partisan ‘home’ juries.

Attempts by Irish parliamentarians to imply that, despite his fearsome reputation, his presence in Limerick, Clare and Galway had little actual impact on crime statistics, and to suggest that he had signally failed to clear those counties of its ‘hard men’ were brushed off by W.E. Forster’s successor as chief secretary, George Otto Trevelyan. Trevelyan, in response to gibes from Irish MPs that Lloyd had been merely abrasive and autocratic while being simultaneously ineffective, pointed out that, before his appointment in 1882, ‘outrages’ in Clare in the last quarter of 1881 had been at a high of 148. By the spring of 1882, three months after Lloyd’s appointment, they had declined to 86. Results in Limerick, another county within his tri-county bailiwick, had been similar.

Whether or not Lloyd felt that his continued presence in Clare, Limerick and Galway was rapidly becoming counterproductive, given increasing local and national antagonism towards him; whether he became disillusioned after the apparent concessions of the Kilmainham Treaty and the principled resignation of his patron, William E. Forster; or whether he had simply had enough of the threats and the constant strain of his work, Lloyd began to seek alternative employment in May 1882. Nothing was forthcoming from a government that, in light of the Phoenix Park murders and the passage of the draconian Crimes Act, was not yet ready to dispense with his services in Ireland. Towards the end of 1882 he again applied for a transfer. It was not until the middle of 1883, when the government reorganised the magistracy and dispensed with the role of Special Resident Magistrate, that Lloyd was allowed to move on.

He was retained pro tem as an ordinary magistrate but he secured extended leave to work in the Egyptian police and prison system. Nationalist newspapers gloated over his departure, and raised raucous protests at his precipitate return when his Middle Eastern idyll did not work out. United Ireland, coming up with yet another imaginatively scornful appellation for Lloyd (‘tyrannical bashaw’) crowed at his minor humiliation in having proved unacceptable to the Egyptian authorities. ‘Mr Clifford Lloyd,’ O’Brien exulted, ‘is not to rid Ireland of his presence after all. The cholera is too virulent in Egypt at present for gallant heroes of the SRM type’.[16]Lloyd was reassigned to Derry as an ordinary RM, an apparent demotion, while, like Mr. Micawber, he waited for something to turn up. In 1885 an opportunity finally presented itself. It was not the colonial governorship to which he aspired, and which he felt was his due, but the lieutenant-governorship of the island of Mauritius. There he quickly fell foul of the Irish-born governor and future nationalist MP for Kilkenny, Sir John Pope Hennessy. After transferring to the Seychelles, Lloyd resigned from the colonial service in 1887. He died prematurely of pneumonia, six days shy of his forty-seventh birthday. While historian Stephen Ball, an acknowledged expert on nineteenth century policing policy, describes Lloyd as ‘perhaps the sternest of Forster’s Special Resident Magistrates’,[17] the chief secretary’s daughter, Florence Arnold-Forster, herself beguiled by both Lloyd’s personality and his methods, acknowledged that ‘with all his vigour Mr. Lloyd is a little too impulsive, too much up and down’. Her father placed more trust in one of Lloyd’s four SRM colleagues, Captain Plunkett (‘Pasha’ Plunkett to United Ireland) who would continue to function as a resident magistrate well into the Plan of Campaign era of the late 1880s. ‘Father is inclined to think Mr. Plunkett is the best for his work’ Florence confided to her diary in February 1882 after a long walk with her harassed

parent.[18]

Lloyd may well have been more mercurial and not quite as quietly efficient as the more durable Plunkett, but his profile, during his brief tenure in his specialist role as a potent stipendiary magistrate, was higher than that of his colleague. His acerbic and unsurprisingly self-aggrandising memoir of the Land War—which devotes much space to his rivalry with a combative Eugene Sheehy—reveals a man of considerable moral and physical courage whose determination to maintain law and order was as strong as his obsession with the preservation of the prevailing status quo in rural Ireland. Clifford Lloyd was never plagued by self-doubt, neither was he a public service cipher or a disillusioned mercenary. He was a champion of the rights of private property who deprecated the impertinence of the Irish peasantry, affluent and indigent alike, in seeking the overthrow of their landlords. His undiscriminating vigour; his penchant for tarring political activism and agrarian violence with the same brush; and his proclivity for aggressive policing rather than diplomacy, rendered him a rapidly wasting asset to a government whose ‘Kilmainham Treaty’ May 1882 volte-face (notwithstanding the introduction of the Crimes Act after the Phoenix Park murders) signalled a desire for accommodation rather than confrontation. An assertive magistrate with Lloyd’s record became supernumerary once the Liberal government chose compromise over conflict.

Lloyd, however, remained unrepentant. His valediction in Ireland Under the Land League was stark and unapologetic. ‘Blood the Land League wanted,’ he wrote in the final paragraph of his memoir, ‘and blood it caused to flow, with a cruelty and savageness unsurpassed in history’.[19] It was typical hyperbole from a distinguished member of the establishment officer corps, but it contained more than a grain of truth.

[1] Clifford Lloyd, Ireland Under the Land League, (London, 1892), 60-61.[2] Lloyd, Ireland Under the Land League, 70.[3] Edith Somerville and Martin Ross, The Irish RM and his experiences (London, 1948), 7. [4] Lloyd, Ireland Under the Land League, 44, 226, 27, 81, 97, 89-90.[5]T.W.Moody and R.A.J.Hawkins (eds.) Florence Arnold-Forster’s Irish Journal (Oxford, 1988), 465, 254.[6] United Ireland, 7 January 1882. [7] Lloyd, Ireland Under the Land League, 92. [8] HC Deb 10 August 1882 vol 273 cc1414-70. [9] Clare Independent, 25 February 1882.[10] Clare Freeman, 18 February 1882. [11] Moody and Hawkins, Florence Arnold-Forster’s Irish Journal, 345.[12] Lloyd, Ireland Under the Land League, 99-100.[13] Clifford Lloyd to Sir Robert Hamilton, 2 Sept 1883, NAI CSORP 1883/2040.[14] Lloyd, Ireland Under the Land League, 101.[15] HC Deb 04 May 1882 vol 269 cc.95-695.[16] United Ireland, 11 August 1883.[17] Stephen Andrew Ball, Policing the Land War: Official responses to political protest and agrarian crime in Ireland 1879-91 |(PhD thesis Trinity College, Dublin, 2000), 30. [18] Moody and Hawkins, Florence Arnold-Forster’s Irish Journal, 382.[19] Lloyd, Ireland Under the Land League, 243.

You must be logged in to post a comment.