Agistment

The process of bringing livestock to pasture. In 1735 the House of Commons effectively removed the ‘tithe of agistment’ thus ensuring that beef and milch cattle were exempt from tithes. This had the effect of shifting the burden from wealthy graziers to tillage and subsistence farmers.

Approver

An accused party offering evidence against his co-conspirators in a crime, in return for full or partial amnesty.

Back to the Land

A co-operative movement that emerged in the early years of the 20th century, raised its own finance, and purchased estates for division among small farmers and landless labourers.

Bailiff

An official whose function was to effect the eviction of a tenant and, if required, sequestration of the tenant’s ‘removables’ (furniture etc.).

Bessborough Commission

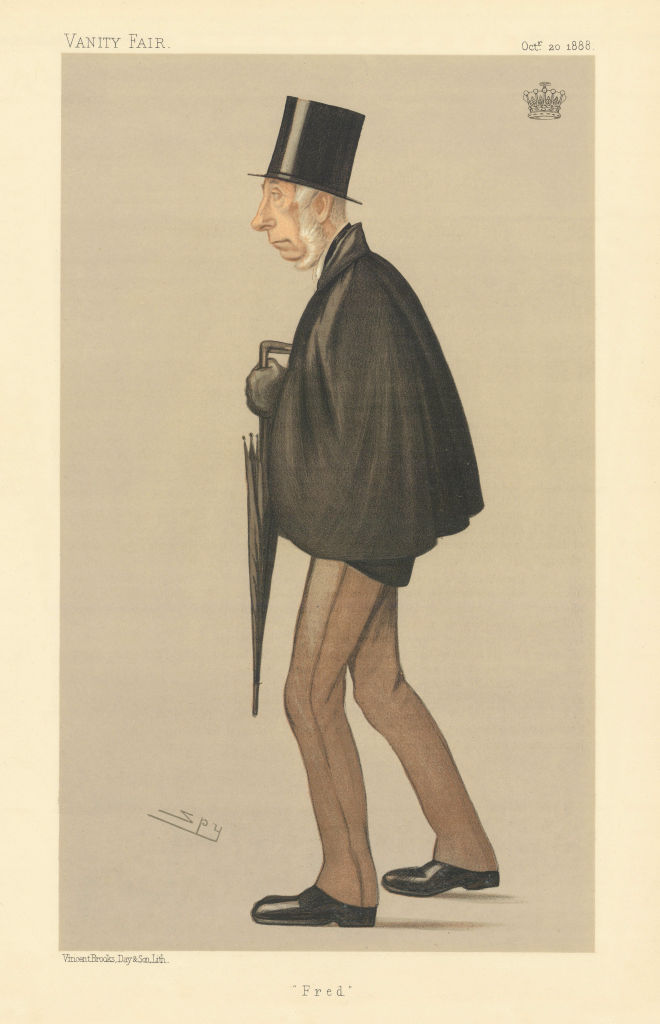

Appointed in 1881 to inquire into the working of the 1870 Land Act and chaired by Frederick Ponsonby, 6th Earl of Bessborough. Its books of evidence offer a valuable insight into rural Ireland during the Land War. The Commission essentially offered support for the Land League (qv) demands for the 3Fs (qv), the only dissenting commissioner being the landlord representative, the idiosyncratic Arthur McMurough Kavanagh, the limbless former MP and Lord Lieutenant of Carlow.

Frederick Ponsonby, 6th Earl of Bessborough

Blackfeet

A Whiteboy variant that emerged in south Leinster in the 1830s.

Board of Works

Established in 1831 the Board of Works spent £49m on public works projects up to 1914.

Boycotting

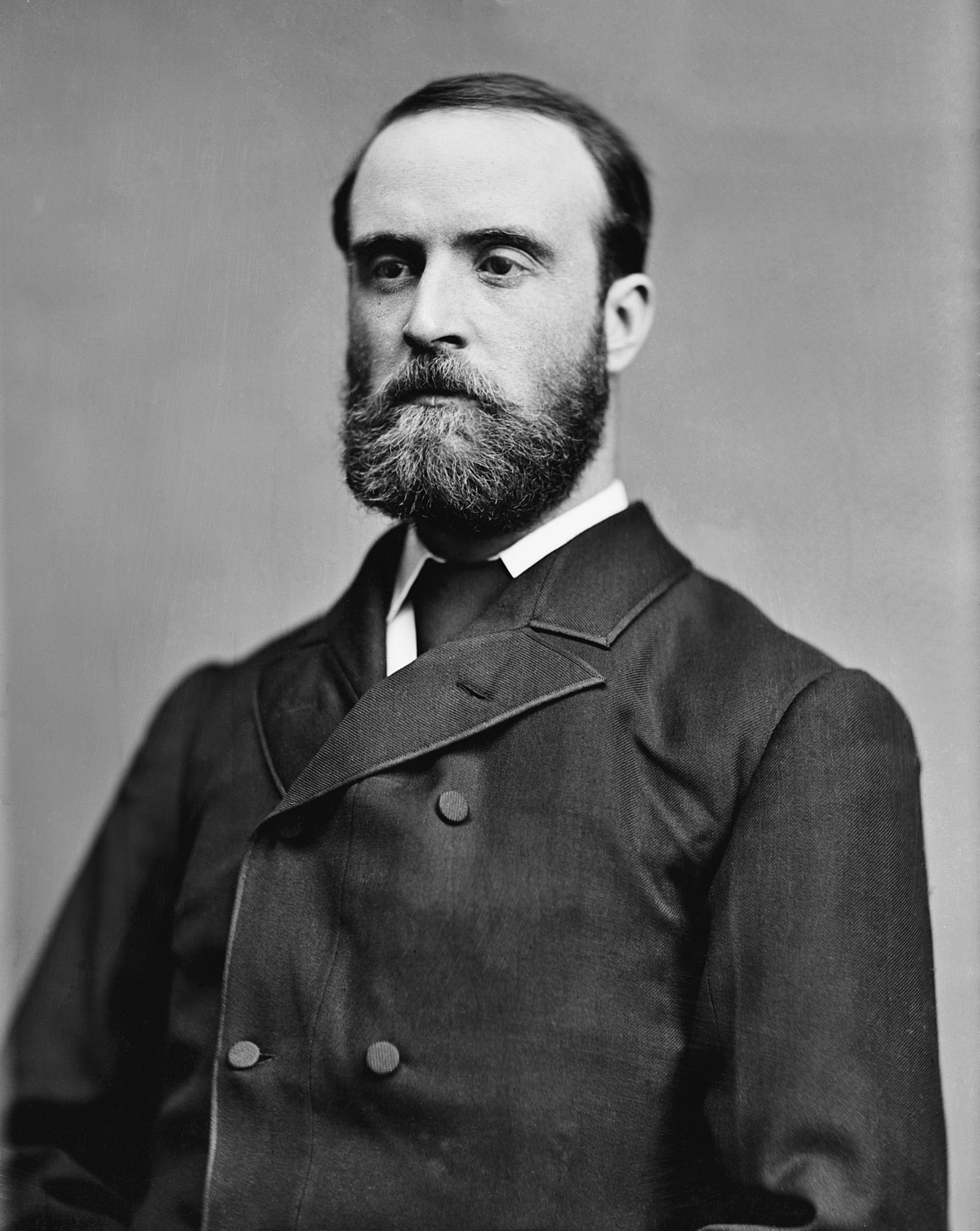

The despatch of an obnoxious tenant, agent, landlord or ‘grabber’ (qv) to a ‘moral Coventry’. A process of ostracization generally seen to have been initiated in 1881 but actually a longstanding tactic in Irish agrarian campaigns. Individuals were cut off by their neighbours from all social and economic intercourse. Named for the Mayo land agent Captain Charles Boycott who was its most prominent victim during the Land War of 1879-82 (qv).

Captain Charles Boycott

Canting

The sale by auction to the highest bidder of a farm with a recently evicted tenant or a tenant in the process of being evicted.

‘Captain Moonlight’

A (mostly) 19th century euphemism for agrarian outrages. On being jailed in October 1881 Charles Stewart Parnell famously said that his place at the helm of agrarian agitation would be taken by ‘Captain Moonlight’.

‘Captain Rock’

The mythical figure supposedly behind the Rockite disturbances of the 1820s. During that period many threatening letters bore the signature of ‘Captain Rock’ or ‘John Rock’.

Caravats, the

An agrarian secret society whose antagonism was aimed not at landlords as such, but at large farmers. Their activities from 1806-11 were based in south Leinster (Kilkenny) and east Munster (Limerick, Tipperary, Waterford and Cork) and were opposed by a society of wealthy farmers known as the Shanavests (qv).

Carders, the

An early 19th century agrarian secret society that took its name from the vicious practice of carding (qv).

Carding

An atrocious punishment meted out by members of agrarian secret societies in which nails are driven through a board and this is then drawn across the back of a victim. This method was so extreme that it was eventually abandoned as it was deprecated by most of the supporters of even militant agrarian activism.

Caretaker

A person or persons left to occupy a house after an eviction. The function was sometimes undertaken by bailiffs (qv) or ‘emergency men’ (qv) but often, where an eviction had been carried out largely as a warning to a tenant in arrears, the tenant himself would be left in situ as caretaker. This practice partly accounted for the disparity between permanent evictions and tenant readmissions.

Carrickshock

A townland in County Kilkenny, near Knocktopher where a fracas in December 1831 during the Tithe War led to the deaths of a process server, a dozen policemen and three anti-tithe protestors.

Cattle driving

The practice, particularly notable during the Ranch War (19060-09) (qv), of stealing cattle and ‘driving’ them a considerable distance. Used as a form of protest and intimidation during the Ranch War.

Cess

A tax levied by county Grand Juries for the upkeep of roads and bridges. Excess levels of cess in certain counties or baronies often sparked militant action by agrarian secret societies. The word is still a term of abuse in some parts of rural Ireland, as in ‘bad cess to you!’

Clachán

The community at the centre of land held under the rundale system (qv).

Conacre

The act of renting a small area of land and planting a single crop, generally potatoes.

Congested Districts Board

Established by Tory chief secretary, Arthur Balfour, in 1891 to alleviate poverty in ‘congested’ regions of high population density and few resources in the west and northwest of Ireland. The CDB was dissolved by the new Irish Free State in 1923. An integral element of the Tory policy of ‘killing Home Rule with kindness’ in the 1890s.

‘Congests’

The name often applied to impoverished tenants in general, but in particular to those from areas under the aegis of the Congested Districts Board (qv).

Cottier

Sometimes represented as ‘cottar’, these were generally agricultural labourers or small farmers who rented small plots (c. 1 acre) and planted potatoes thereon in return for their labour. Almost wiped out by the Great Famine.

Cowper Commission

A commission of inquiry into Irish land tenure named for its chair, the former Lord Lieutenant, Earl Cowper, and established by the Tory government of Lord Salisbury. It reported in 1887, recognising that the fall in agricultural prices since the passage of the 1881 Land Act had reduced the ability of tenants to pay even Land Court arbitrated rents.

7th Earl Cowper

Deasy’s Act

Legislation passed in 1860 which altered the relationship of landlord and tenant, to the benefit of the latter. Passed through parliament without amendment, its central principle was that ‘The relation of landlord and tenant shall be deemed to be founded on the express or implied contract of the parties, and not upon tenure or service.’

Devon Commission, the

Its full title was the ‘Royal Commission on the state of the law and practice relating to the occupation of land in Ireland’. It was chaired by the Co. Limerick landlord, William Courtney, 10th Earl of Devon. The commission gathered evidence and compiled its report between 1843 and 1845. Its central recommendation, that ‘tenant right’ be formally recognised by the payment of compensation to outgoing tenants for any improvements made to their farm, was not enacted into law.

Distraint

The seizure of farm produce or implements, for subsequent sale at auction to meet the financial obligations of tenants in arrears to their landlords.

Down Survey

The Cromwellian-era mapping of Ireland under the supervision of Sir William Petty.

Sir William Petty

Driver

A bailiff employed to drive distrained cattle to the pound. The term could also apply to a Ranch War-era moonlighter (qv) who ‘drives’ a grazier’s cattle from pasture land onto the roads. The former was generally reviled by small tenant farmers, but operated within the law. The latter did not, but was generally revered by small tenant farmers.

Duty days

An obligation sometimes owed by a tenant to a landlord. The tenant was required to work on a set number of days per annum. A particularly vindictive landlord would demand his duty days at a time when a tenant needed to bring in his own harvest, in order to pay his rent. The fictional Thady Quirk refers to such punishments in Castle Rackrent by Maria Edgeworth.

‘Eleven month’ system

A device frequently used to get around the tenant-oriented land legislation of the 1880s and 1890s. Land was auctioned on an annual basis and the highest bidder was then allowed the use of the land for eleven months. The system encouraged wealthy merchants and professionals to purchase, graze and sell herds of livestock.

Emergency men

A generic term for those offering their services as bailiffs (qv), or often as caretakers left in the houses of evicted tenants to ensure that their former occupants were unable to re-possess. The name is derived from one of the landlord bodies, the Orange Emergency Committee, which opposed the activities of the Land League during the Land War, and those of the Irish National League during the Plan of Campaign.

Enclosure

The act of fencing off common land previously available to all members of a community. Most common land in Ireland and Britain had been enclosed by landowners by the end of the eighteenth century.

Encumbered Estates Acts

Passed in 1848 and 1849 this legislation established the Encumbered Estates Court, which allowed the sale of the estates of landlords rendered insolvent by the Great Famine. Designed to encourage a new wave of British owners of Irish land, in fact much of the almost five million acres that changed hands went to wealthy Irish Roman Catholic landlords, often Dublin-based professional men.

‘English tenant’

This has nothing to do with nationality but referred to a tenant who was required to pay his rent on the day it was due, rather than on a ‘gale day’ (qv) six month in arrears, as was the Irish custom. It could be used, for example, as a punishment by a landlord in the case of a tenant who had not voted as instructed in an election. He could be required to become an ‘English tenant’, i.e. immediately pay six months arrears of rent.

Gale days

The bi-annual period during which tenants paid their rent, generally to a landlord’s agent. The two annual gale days tended to be in May and November.

‘Grabber’

Or ‘land grabber’. Generally a tenant farmer who took over the land vacated by an evicted tenant. Many were threatened, injured or murdered. The phrase acquired particular currency during the Land War (1879-82). It later came to be applied to those illicitly seizing land during the Anglo Irish War and the subsequent Civil War.

Graziers

Farmers (and non-farmers) who rented extensive tracts of pasture land and raised cattle or sheep. This type of husbandry was anathema to small farmers and landless labourers because of the usage of what might otherwise have been arable land, available to rent. Graziers were also known (and not in a positive way) as ‘ranchers’.

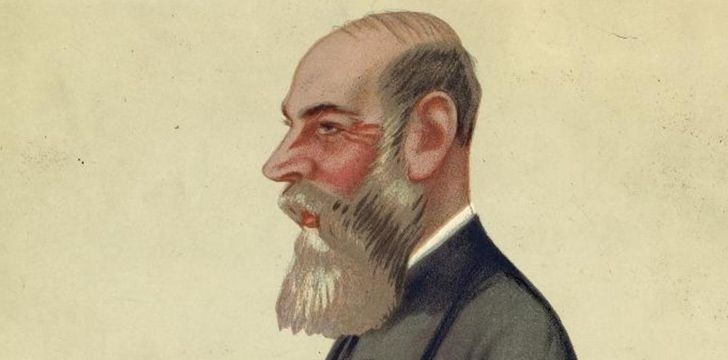

‘Griffith’ valuation

Named after Richard Griffith, Commissioner of Valuation in Ireland from 1827 until 1868. Griffith was the man primarily responsible for mapping and valuing, for taxation purposes, the land of Ireland from the 1830s to the 1860s.

Richard Griffith, Commissioner of Valuation (1827-68)

Hanging gale

The first six month period (May-November or November-May) of a tenancy after which the tenant was obliged to pay his first portion of rent.

Hearts of Oak

An 18th century agrarian secret society that emerged in Armagh in 1763 in opposition, at first, to a legal obligation on the part of tenants to work on road construction. After a few weeks of protest activities and muted violence the ‘Oakboys’ disbanded in the face of military opposition.

Hearts of Steel

A more sustained—it continued in existence for three years—and coherent movement than the ‘Oakboys’ which emerged in Antrim and Down and was originally founded in opposition to ‘fines’ imposed on the estate of Lord Donegall on tenants who wanted to renew their leases. The ‘Steelboys’ often operated openly and they successfully attacked a Belfast barracks (1770) and Gilford Castle (1772).

Heriot

A landlord right, deriving from an old medieval custom, to the use of a tenant’s horse at short notice.

Houghers

An early agrarian secret society (1711-12) based in Connacht and opposed to the use of land for the purpose of grazing livestock. Named for one of their favoured methods of protest, the maiming of cattle.

Houghing

Maiming cattle in order to intimidate their owner. The cattle would be lamed by severing their hamstring tendons.

Improving landlords

Something of a ‘catch-all’ phrase covering everything from landlords wishing to divest themselves of tenants in order to ‘work’ their own estates, to landlords intent on either enhancing the lot of their tenants by undertaking ‘improvements’ to their land, or the introduction of progressive and more scientific farming methods. ‘Improving’ landlords (the term often appears in quotation marks to suggest a degree of historiographical scepticism of the breed) were often as welcome to the tenant as a bad toothache.

‘Kilmainham Treaty, the’

An unofficial agreement brokered by Captain William O’Shea between the incarcerated Charles Stewart Parnell and British prime minister William E. Gladstone. The Liberal government agreed to introduce an act of parliament allowing tenants in arrears access to the newly established Land Courts, and Parnell agreed to use his ‘influence’ to end agrarian disorder and ‘outrage’.

Captain William O’Shea

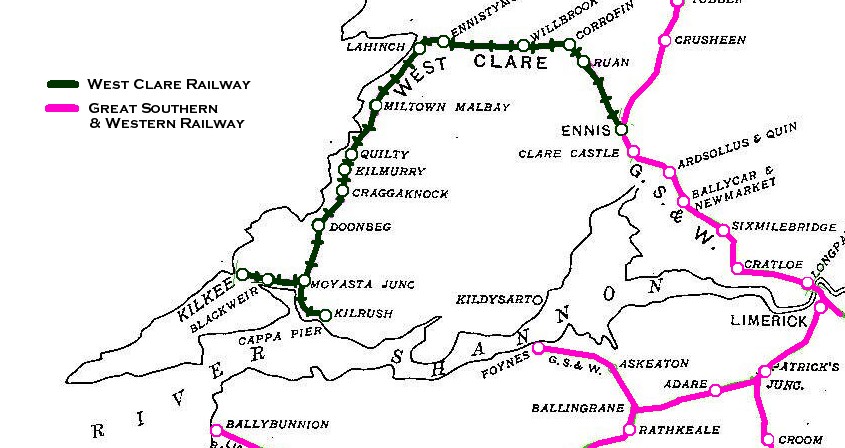

![train-clare[1].jpg](https://mylesdungan.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/train-clare1.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.