There are spies, there are informers, there are traitors, and then there is Leonard McNally. He was one of the most effective and enduring British spies in the ranks of an Irish revolutionary organisation. The unlucky, or careless, rebels were the United Irishmen, the men of 1798.

McNally, a barrister and playwright, was actually a prominent and radical member of the United Irishmen. He was eager for the organisation to accept military assistance from revolutionary France. But when William Jackson, an agent of the French government, was arrested in Ireland in 1794, McNally, rather than wait to be shopped for treason by Jackson, took a more pro-active course and offered his services to the Crown in exchange for not being hanged, drawn and quartered. Given what actually happens to someone who is hanged drawn and quartered he might well be forgiven for this initial capitulation. But the fact that he was still providing intelligence to Dublin Castle a quarter of a century later suggests that it had become more about remuneration than self-preservation.

After the 1798 rebellion McNally defended many United Irishmen charged with involvement in the abortive insurrection. He didn’t win a single case. It could have been because his clients were guilty to begin with, or because he was fiendishly unlucky. But his winless streak was more likely to have been related to the fact that he was passing information on his clients to the prosecution. Not really the done thing for a defence attorney I’m sure you’ll agree.

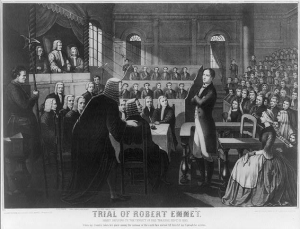

Among the men he defended were William Jackson, Wolfe Tone, Lord Edward Fitzgerald and, in 1803, Robert Emmet. So, were there an Irish Pantheon he would probably have contributed to the presence of about half the occupants. In the case of Emmet he advised the Crown that his client would enter no defence and allow cross examination of no witnesses on his behalf, as long as they did not misrepresent the facts. So the trial would be a walkover for the prosecution and Dublin Castle didn’t even have to bother fabricating evidence that might come back to haunt them in court.

After 1803 you’d have thought McNally would have quietly and gracefully retired. But a £200 bonus, on top of his hefty pension of £300, ensured that ‘JW’, the code name by which he was known to his spymasters, stayed in business until his death in 1820.

In a doubtlessly fruitless effort to mitigate McNally’s evil reputation it should be pointed out that he was also a successful playwright and librettist. One of his songs, The Lass of Richmond Hill, became a huge hit in its day, 1789, and a favourite of King George III, the one who had occasional bouts of madness. It was written about McNally’s first wife Frances and describes her as ‘a rose without a thorn’.

In one of those wonderful ironies for which a fiction writer would be pilloried were it to appear in a novel, a legal treatise, written by McNally the year before his betrayal of Robert Emmet, was pivotal in the definition of the principle of guilt being ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ before conviction.

His espionage activities did not become apparent until after his death when his son sought to have the payment of his pension continued post mortem. When the Lord Lieutenant inquired as to why a pension had been paid to such an ardent nationalist, the truth began to emerge.

Leonard McNally, barrister, playwright, serial informer and a rose with many thorns, died 195 years ago, on this day.

You must be logged in to post a comment.