It was an élite unit established with a single intention, to kill.

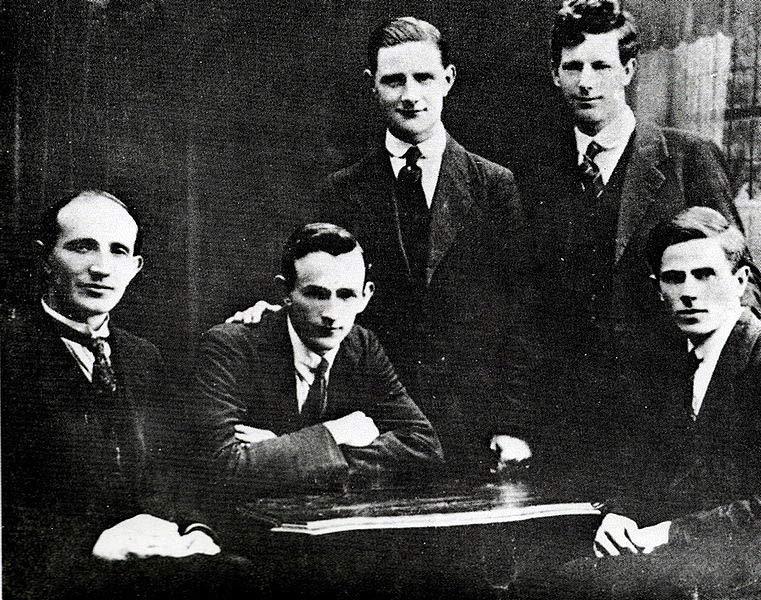

Known colloquially as ‘The Twelve Apostles’, and by its own members, as ‘The Squad’ it was established with the sole purpose of carrying out the ‘executions’ of spies, informers, British agents, and Dublin policemen identified by the IRA’s own spies, informers and agents in GHQ Intelligence under the tutelage of Michael Collins and Liam Tobin.

Among its major sanguinary coups were the murders of DMP District Inspector William Redmond (21 January 1920), Resident Magistrate Alan Bell (26 March 1920) , the British spy John Charles Byrne(s) aka ‘John Jameson’ (March, 1920). Along with elements of the Dublin Brigade of the IRA the Squad also participated in the devastating ‘Bloody Sunday’ killings (21 November 1920). In that notorious operation between six and twelve imported British agents (the number of actual agents v collateral damage is disputed – but that’s an argument for another day) were assassinated on the morning of the bloodiest single twenty-four hour period in the history of the Anglo-Irish conflict.

One of the Squad’s principal antagonists, Dublin Castle spymaster Ormonde Winter (he wore a monocle that made him look more spymastery) imported fifty bloodhounds from England in an attempt to track down some of Collins’s professional (£4.10s a week) killers. That’s actual, not metaphorical bloodhounds. A convenient and well-advertised postal address in London, to which confidential information could be sent about the Squad’s membership–and anything else you might happen to know about the IRA—was ‘punked’ by Sinn Féin supporters who flooded it with letters pointing to leading Irish loyalists as republican terror suspects. Well what did they expect?

But who was the original leader of this carefully chosen elite unit?

You would think that an examination of the testimony of members of the Squad given to the Bureau of Military History in the late 1940s and 1950s would provide a straight answer to that question. In fact any such examination simply muddies the waters and leaves the reader scratching his head.

There are two candidates for the position, Mick McDonnell and Paddy O’Daly. Both have claimed the title, and in the case of O’Daly – who did lead the unit at one point—he even went so far as to deny that his rival claimant was ever a member of the Squad! Received wisdom has it that the leadership sequence went as follows, Mick McDonnell (late-1919 until mid-1920 when he emigrated to California), Patrick O’Daly (aka Paddy Daly) from the time of the departure of McDonnell to the USA until his own arrest in late November 1920, Jim Slattery as third Captain until the Custom House operation in May 1921 (in which he was wounded) effectively brought the days of the Squad to an end. However, there is also a variant of this received wisdom which has Slattery taking over from McDonnell and being succeeded by O’Daly. But surely the Bureau of Military History Witness Statements can sort out all anomalies? You’d think!

It is clear that both McDonnell and Daly were leading figures in the creation of the original group which—in an egregious example of Irish black humour—became known as the ‘Twelve Apostles’ because, although membership was never static, the ‘settled’ unit numbered a dozen young acolytes (with Collins as Redeemer) who were prepared to work well outside the remit of the ‘rules of engagement’.

It’s even difficult to establish a consensus when it comes to the precise origins—never mind the original hierarchical structure—of the Squad. As the ‘Apostles’ were not altar boys they weren’t exactly expected to be religious in their record-keeping. Successful ‘hits’ were not entered into a daily duty ledger. Most of the original members were sought out and interviewed, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, by the researchers of the Bureau of Military History, three decades and more after the life-changing events (life-ending for many of their targets) in which they had participated. Memories were on the wane, a lot of vinegar had passed under the bridge, egos had been inflated by years of official adulation, and reputations had to be protected for posterity.

So, when you read those statements there is very little agreement, more than thirty years after the event, about even the most basic questions, such as the ’where’, the ‘when’ and the ‘who’. Was the nascent Squad established in Parnell Square or Georges Street? Was it set up in May or September 1919? Were Michael Collins, Richard Mulcahy and Dick McGee present at the initiation? Was the killer with the choir boy looks, Vinnie Byrne, at the inaugural meeting (wherever and whenever it took place) or was he recruited shortly afterwards?

If such basic facts cannot be ascertained, where does that leave us with the more fundamental question about who was the man originally put in charge by Collins?

Mick McDonnell was certainly in no doubt about who was the first O/C of the Squad. In his BMH-WS (#225, p2) he talks about being appointed Captain / Quartermaster of the 2nd Battalion of the Dublin Volunteers shortly after his release from Frongoch prison camp in North Wales. He then adds, ‘I remained with the 2nd Battalion until I took over the Squad early in 1919.’ He insists the unit was established on 1 May 1919, but did not become a full-time, wage-earning team until 1920, probably just prior to his departure from Ireland.

He is also unambiguous about being in command of the operation which, had it been successful, would have constituted the biggest single Squad coup of the Anglo-Irish War. This was the 19 December 1919 attempt on the life of the Lord Lieutenant, Lord French, near Ashtown railway station, adjacent to Phoenix Park. McDonnell laid claim to the execution of that operation (a claim supported by others). ‘I was in charge of that ambush’ he insisted in his 1949 statement. He talks about issuing instructions to Paddy O’Daly – ‘I put Paddy Daly [sic] and four others inside the hedge with hand grenades … telling them to concentrate on the second car …’

Equally emphatic, however, was Paddy O’Daly (who often appears in witness statements as plain ‘Daly’ but who signed his April 1949 statement as ‘O’Daly’). O’Daly had a distinguished career in the Anglo-Irish War and a controversial one in the fratricidal Civil War that followed. At the outset of the Civil War, Daly was the officer who refused to stop firing on the Four Courts in order to allow the Dublin Fire Brigade access to douse the flames that threatened the famous Gandon-designed landmark. He is supposed to have responded to the Chief Fire Officer, who made the request for a temporary ceasefire to help preserve the fabric of the building, that, ‘Ireland is more important than the fire at the Four Courts’.

As commander of the National Army forces in Kerry in 1923 he gained a reputation for ruthlessness. Soldiers under his command were responsible for some of the worst atrocities of that atrocious conflict. O’Daly is reputed to have said, ‘No one told me to bring any kid gloves, so I didn’t bring any.’ That he certainly didn’t. One of his ‘iron fist’ tactics was to force Republican prisoners to clear roads that were suspected of having been mined. National Army troops under his command were responsible for the horrific murders of eight Republican prisoners, blasted and machine-gunned to death at Ballyseedy in north Kerry.

O’Daly, in his second BMH-WS (#387 p 11) claims that the Squad was formed on 19 September, 1919 with Michael Collins and Richard Mulachy in attendance. A number of carefully selected Volunteers had been summoned to 46 Parnell Square (then known as Rutland Square) by 2nd battalion commandant Dick McKee. According to O’Daly’s account these were himself, Joe Leonard, Ben Barrett, Seán Doyle, Tom Keogh, Jim Slattery, Vinny Byrne and Mick McDonnell. However, according to Daly, ‘Michael Collins picked only four of us for the Squad that night, Joe Leonard, Seán Doyle, Ben Barrett and myself in charge.’

There were twelve ‘Apostles’ for most of the Squad’s operational phase (probably eight at the outset and an indeterminate number before the unit was rolled into the Dublin Guard after the Custom House debacle) – but there could only be one St. Peter. So, was it O’Daly or McDonnell? They can’t both have been telling the truth, the whole truth, etc.

Or can they? In the early days of the conflict, were there two squads?

While recollections after thirty years can be faulty or suspect the two contradictory statements smack of special pleading. McDonnell makes almost no reference to Daly other than in entirely subaltern role in the attempt on French’s life. O’Daly, however, appears to set out to discredit McDonnell and devalue his contribution to the Squad narrative. He even claims (see below) that McDonnell was never even a member of the Squad!

So, what do the witness statements of others involved in the operations of the Squad tell us about the chain of command? Do they clarify the status of McDonnell or O’Daly? Not really – they often merely add to the confusion.

Among the more prominent members of the Squad to have left witness statements, when approached to record their memories in the late 1940s and early 1950s, were Mick McDonnell, Paddy O’Daly, Jim Slattery, Joe Leonard, Vinnie Byrne, Charlie Dalton (mostly an ex officio member) and Bill Stapleton (who was only recruited after Bloody Sunday and who testified that ‘I believe a principal mover in the original Squad was Mick McDonald [sic]’- (BMH-WS #822, p.31).Of the others whose names often feature in the Squad’s foundation mythology, Seán Doyle was killed in the attack on the Custom House on 25 May 1921, Tom Keogh died in the Civil War, Ben Barrett, whose mental health broke down because of his involvement with the Squad (a personal tragedy he shared with Charlie Dalton) died in 1946, before the BMH could tap into his memory. However, Barrett applied for a Military Pension in 1924 citing O’Daly, not McDonnell, as the O/C of what he described as the ‘Special Squad (the original ASU)’ (W24SP138)

In his statement, BMH-WS #547, Joe Leonard confirms O’Daly’s version of events. He persists in calling McDonnell, ‘McDonald’ (he would have been given an opportunity to correct any errors in transcription of his testimony), acknowledges that the 2nd Battalion quartermaster was one of those at the top table of the inaugural meeting of the Squad [which he puts in ‘September’ in ‘44 Parnell Square’] and insists that O‘Daly was given command of the unit. He claims that McDonnell, Tom Keogh, Jim Slattery, and Vincent Byrne ‘wanted to join us but would not be allowed on that occasion as they were required elsewhere on their own work.’ He further claims that on the occasion of the attempted assassination of French, that McDonnell, Keogh, Slattery and Byrne were mere additions to the Squad’s retinue and not core members, (as was also the case with the Tipperary ‘Big Four’, Treacy, Breen, Robinson and Hogan, ‘on the run’ in Dublin at the time, who also took part – Breen was wounded) and that O’Daly was in charge of the operation.

It is the statement of Charlie Dalton, who was occasionally associated with the Squad before moving to the Intelligence Staff, that offers some clarification on the hierarchy within the unit. While Mick McDonnell did not live to make a promised second statement to the BMH, he had already made a prior statement to Dalton in 1948. On a visit from California that year he spent an evening with Dalton, who told the BMH in his own statement, that they passed some time ‘discussing matters about which he [McDonnell] said he would like me to have the correct facts.’ (BMH-WS #434, p40) That conversation completely revises the foundation myth of the Squad. McDonnell referred to a meeting of ‘selected Volunteers’ (as many as twenty) that took place at 42 North Great George’s Street. Those assembled were asked would they be willing to shoot members of ‘G’ division. ‘Most of those present refused to give an affirmative answer’ McDonnell told Dalton. However, he, Slattery, Keogh (McDonnell’s half-brother) and ‘probably, Vincent Byrne’ ‘stepped out of the ranks’ and expressed their willingness to become assassins.

Dalton told the BMH that in the course of his own association with the Squad he took his orders from McDonnell, but added that ‘I learned that in the initial stages a few jobs were carried out independently by Paddy Daly [sic], Joe Leonard and Ben Barrett … this would suggest that two squads operated in the early stages.’

Vinnie Byrne—who also took his orders from McDonnell in 1919-20, and definitely saw him as the leader of the Squad— adds a few wrinkles of his own by suggesting that he was not at the Parnell Square September meeting O’Daly described, or McDonnell’s alternative gathering in North Great George’s Street, but that his induction came at the end of November 1919 (probably 28 November) in McDonnell’s own house. There, while sitting at the fire with Jim Slattery and Tom Keogh, Byrne attested that he was asked directly by McDonnell ‘Would you shoot a man, Byrne?’ When the name of G-man, Detective John Barton was mentioned Byrne, who had ‘previous’ with Barton, rapidly shed any scruples he might have had about close-up assassination. That was how Byrne found himself involved in the first of many IRA ‘hits’ the following day.

Byrne’s testimony, however, (backed up in some details by that of Joe Leonard – BMH-WS #547, p.4)) does confirm why both O’Daly and McDonnell might have seen themselves as the major domo of the Squad, and, indeed, why, for a short period at least, both would have been entitled to view themselves thus. This is because, on the day he was murdered, Detective Johnny Barton was being dogged by two IRA hit squads, one led by McDonnell, the other by O’Daly. Often the Squad would divide itself in two, half acting as ‘shooters’ and the other half as ‘scouts’. But this was different. Each unit was unaware of the presence of the other until both had spotted and were following Barton. Neither Byrne nor Leonard specifies who fired the fatal shot that killed Barton as he approached DMP ‘G’ Division Headquarters in Great Brunswick Street (now Pearse Street Garda Station).

Byrne is far more specific when he discusses the chain of command in Ashtown on 19 December 1919. As far as Byrne was concerned McDonnell was in command of the attempt on the life of Lord French.

Jim Slattery’s statement (#445, p.2) probably reflects his personal attachment to McDonnell as much as Leonard’s indicates his own close relationship with O’Daly. Slattery was at McDonnell’s meeting in North Great George’s Street (No.35) where McDonnell and Dick McKee were calling the shots. There is no mention of Collins or Mulcahy being present. When the question was put by McKee and McDonnell about the potential assassination of DMP ‘political’ detectives, among those who did not demur, according to Slattery, were the witness himself, Tom Ennis (the first mention of Ennis as an original member of the Squad), Tom Keogh, O’Daly and Leonard.

Slattery also made reference to the sub-division of the early Squad. He answered to McDonnell—‘I looked upon him as the officer in charge of the section to which I was attached’—but acknowledged the existence of a separate unit under Daly. He recalled how McDonnell’s unit was ordered to kill the bothersome Detective Sergeant Patrick ‘The Dog’ Smith (Smyth)—this was done, not very expeditiously, on 30 July 1919, near his Drumcondra home. Smith survived being hit by a number of .38 bullets and died some days later, causing the balle de fusil du jour to become the .45 from then on. A .45 bullet could stop a horse, the .38 barely despatched the ‘Dog’, whose son watched his father being mown down near their house. (I mention that detail lest we get too sentimental about what Collins et al were asking the Squad to do)

Meanwhile, O’Daly’s platoon was sent after DMP Detective Daniel Hoey. Ironically it was Mick McDonnell who ended up murdering Hoey rather than O’Daly’s section. O’Daly acknowledged this in his witness statement (#387, p.11) before adding gratuitously that:

‘ Mick McDonnell was one of the best men in Dublin but he had one fault. He was always butting in, and on account of that he often did damage because he was too eager. He was not a member of the Squad.’

Which is patent nonsense and detracts, perhaps fatally, from the credibility of this element of O’Daly’s statement at least. When O’Daly made his two statements to the Bureau of Military History (#220 and #387) he had begun to mythologise his own role in the War of Independence. O’Daly’s claim is in stark contrast to the account left by Jim Slattery where Slattery avers that, ‘I took over control of the Squad after Mick McDonnell left’, which suggests that the actual sequence in which command of the Squad was assumed went – McDonnell, Slattery, O’Daly.

Please try and keep up down the back.

None of which really helps us much with the basic question, who was the St. Peter, the capo, the primus inter pares, of the original Squad when it undertook complex operations like the assassinations of DI Redmond and RM Alan Bell. Was it Mick McDonnell or Paddy O’Daly? The BMH-WS evidence, such as it is, either ignores the question entirely or reflects the personal affiliation to the two men of their subordinates. While each of the two potential ‘captains’ may have been in charge of a distinct section in the early days of the Squad, which of the two platoon commanders assumed the overall leadership when Collins decided it was time for his hit men to abandon their jobs and go full-time? It appears that you have to pay your money and take your choice. There is nothing definitive in the BMH witness statements of Squad veterans and, given the nature of the beast, there is little contemporary documentation covering the activities of what was a highly secretive and covert assassination squad. The members of the Squad did not walk the streets of Dublin carrying battle orders or regimental diaries in their jacket pockets which were later painstakingly archived. Most of the ‘archive’ was located between the prominent ears of Michael Collins. Some of the participants did write memoirs. Good luck with those. They were intended to be read in their own lifetimes. At least the BMH witness statements were not going to see the light of day until well after they were all dead.

If it was McDonnell who assumed overall command—and that is my own gut feeling—his leadership role was short-lived. By the autumn of 1920, well before the defining coup of the Anglo-Irish War—the Dublin assassinations of 21 November 1920—McDonnell was living in California.

Over the years there has been much speculation about the reason for McDonnell’s abrupt departure from Ireland in 1920. Was he sent on a secret mission to the USA by Collins? Was he exiled because of stress brought on by the death of Volunteer Martin Savage in the abortive attempt on the life of French, and because he was having an extra-marital affair, as alleged in his book on the Squad by Tim Pat Coogan. Coogan goes on to claim that Tom Keogh and Vinnie Byrne set out to kill McDonnell’s inamorata, or ‘that Jezebel’ as they referred to her.

McDonnell himself offers no explanation in his witness statement as to why he emigrated to the USA, where he ended up on the west coast. Coogan refers to his work for the McEnery family, and specifically for John P. McEnery, Superintendent of the United States Mint in San Francisco.

John McEnery’s son Tom, twice mayor of San Jose, is in no doubt whatever as to why McDonnell abandoned Ireland and travelled to California. It was to arrest the spread of a debilitating case of tuberculosis. Had McDonnell remained in Ireland in 1920 he might have been mown down, not by triumphant Auxiliaries or G-man, but by consumption.

At some point during the (War of Independence/Civil War) McDonnell must have felt that he had sufficiently recovered to return to the fray and wrote accordingly to Collins. The McEnery family still retain the response of Collins in their archive. McDonnell was told to stay where he was and look after his health. ‘Stay there with the fruit and sunshine and get healthy,’ wrote Collins with obvious affection for his former lieutenant, ‘I’ll let you know if I need you.’ In his missive Collins also made reference to Keogh and Leonard and told their erstwhile captain that both men were doing well.

Tom McEnery has also told me that a drink problem, developed to help cope with what we would now call post traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD), contributed to McDonnell’s death in Los Gatos in 1950. He has made a detailed study of McDonnell’s life, is currently writing a play on McDonnell’s participation in the 1919 IRA plot to murder members of the British cabinet, and is convinced that, as he put it, ‘O’Daly tried to improve himself at Mick’s expense.’

So, to conclude. The original Captain of the Squad might have been Michael McDonnell, Mick McDonald, Patrick O’Daly or Paddy Daly. There might have been two Squads, neither of which, initially, was aware of the existence of the other. There might have been two Squads that regularly collaborated. There might only have been one Squad of eight, twelve, or more members. It was established in May, July and September 1919 in North Great George’s Street and Parnell Square.

I’m glad to have cleared all that up satisfactorily.

You must be logged in to post a comment.