With Elizabeth O’Farrell obscured Minus Elizabeth O’Farrell entirely

It was never going to be much more than a futile gesture to begin with, but few of those in the know, who gathered in Dublin on Easter Monday, 24 April 1916 for Irish Volunteer manoueuvers, would have expected the rebellion they had planned to last as long as a week. The failure of the German steamer the Aud to land 25,000 rifles and a million rounds of ammunition on Good Friday, the arrest of Roger Casement in Kerry and the decision of Volunteer commander Eoin MacNeill to countermand the order for units to assemble on Easter Sunday, had lengthened the odds against the Easter Rising being anything other than a brief skirmish.

That it lasted almost a week was down to British incompetence as much as it was to Irish luck or pluck. Though there were inefficiencies on both sides. While the rebels famously failed to take the wide-open Dublin Castle, the well-positioned Trinity College and the strategically important Crow Street Telephone exchange, the flower of the British administration in Ireland was enjoying the fleshpots of Fairyhouse Racecourse while they were being made fools of in Dublin.

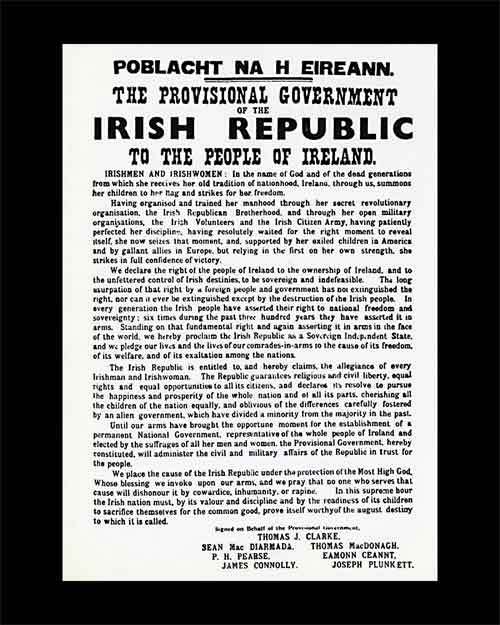

Two myths among many. Patrick Pearse did not read the proclamation of the Irish republic from the steps of the General Post Office. He read it from in front of the building. The GPO, then, and now, doesn’t have any steps. The document he was reading bore the signatures of the members of the Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and James Connolly representing the Irish Citizen’s Army. But it was not their death warrant. The document Pearse was reading was of no use to a prosecutor even in the drumhead courts-martial that followed the rebellion. The reason was simple – the names were printed. The authorities would have had to produce a signed original for it to be of any practical assistance in convicting the signatories.

Most of the fatalities incurred, as the British sought to take back the city of Dublin, were civilians, more than 250 of them. Forty of those were under the age of sixteen. One of the civilian fatalities was the pacifist Francis Sheehy Skeffington, brutally murdered on the orders of an insane British officer, Captain J.C. Bowen Colthurst from Cork as he went about thr city trying to prevent looting. 64 members of the Volunteers or the Irish Citizens Army lost their lives, as did 116 British soldiers. Most of those were from the Sherwood Foresters, picked off on Mount Street Bridge by a small unit sent from the nearby Bolands Mills by 3rd Battalion Commandant Eamon De Valera. When the Forester’s disembarked in Kingstown – now Dun Laoghaire – they were surprised to hear people speaking English. They assumed they’d just landed in wartime France.

James Connolly may or may not have claimed that capitalists would never destroy property even to end a rebellion – he is unlikely to have been sufficiently naïve to have ever said any such thing – but destroy it they did. Much of the centre of Dublin was laid waste by the shells of the gunboat Helga and British artillery stationed in Phibsborough and Trinity College.

The Volunteers’ Headquarters in the General Post Office was never actually taken by the British forces – it was abandoned by the Volunteers before its total destruction by shelling. Shortly after the evacuation of the GPO the rebel leadership bowed to the inevitable six days after the Rising began. That began a busy day for Nurse Elizabeth O’Farrell who was given the dangerous job of informing the other garrisons, most of which remained untaken, that the Rising was at an end.

Patrick Pearse agreed to an unconditional surrender one hundred years ago on this day.

You must be logged in to post a comment.