Land Is All That Matters comes in at around 700 pages. It could have been longer but I agreed to cut a couple of chapters to keep costs down. So, here, over the next few days, is the ‘deleted material’, which, when added back in constitute The Author’s Cut.

THE AGENT

‘Anti-Christ and Orangeman’ – The land agent, Samuel Murray Hussey

‘This Hussey is of English origin and was formerly a cattle-dealer, and practised usury as far back as 1845. If all Ireland were to be searched for a similar despot he would not be found. He is a regular anti-Christ and Orangeman at heart, and, in fact, he acts as agent for all the bankrupt landlords in Kerry.’[1]

(Daniel O’Shea, letter to the New York Tablet, 1880)

The difference twixt moonlight and moonshine

The people at last understand,

For moonlight’s the law of the League

And moonshine is the law of the land.[2]

(Doggerel quoted by Samuel M. Hussey in The Reminiscences of an Irish Land Agent)

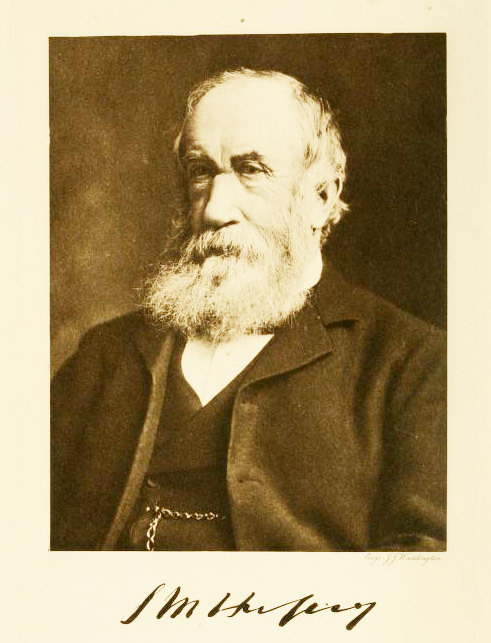

Samuel Murray Hussey

Samuel Murray Hussey’s autobiography, Remininiscences of an Irish Land Agent, appeared in 1904, just in time to allow him to fire off some artillery shells at the Land Purchase Act introduced the previous year by the Tory chief secretary, George Wyndham. No provision had been made for lost agent income in legislation designed to bid adieu to as many Irish landlords prepared to ‘take the shilling’ and depart. The author was suitably aggrieved and didn’t hold back.

Hussey, after the hapless Boycott, is perhaps the best-known agent of the Land War era. Such celebrity in the 1880s was not, of course, a function of popularity. During the Land War, agents were not ‘celebrated’ or ‘famous’, they were, deservedly or not, ‘notorious’ or ‘infamous’.

It is important to get Sam Hussey in some perspective. He was undoubtedly a Land League bete noire, but the raw figures belie his reputation for cold-bloodedness. On the estate of Lord Kenmare, Samuel Hussey’s primary responsibility, permanent evictions (where tenants were not readmitted) between 1878 and 1880 were of the order of 4 per cent of the 2,000 or more tenants. Even in 1880, at the height of the Land War, in the first six months of that year, five tenants out of a total of 4,160 under his agency in Kerry were evicted, and two of those were given paid passage to the USA.[3]However, we should be under no illusion that the relative paucity of evictions on estates under Hussey’s regulation had anything to do with moderation or excessive leniency. Hussey had made a simple economic calculation: there was no income to be extracted from an empty farm, and the power of the boycott had ensured that few if any evicted farms would be occupied in the short term at least. He said as much in his 1904 memoir: ‘Suppose twenty men were tenants on a townland …. Unless caretakers at a cost of about three times the rent were put in under excessive police protection, all the nineteen farms would promptly become derelict’.[4]

Given the low level of eviction on his Kerry estates, why, therefore, was Hussey the most reviled agent in the country at a time when it was open season on members of his profession? The tone of his memoir, Remininiscences of an Irish Land Agent, offers some explanation. Hussey was pugnacious and highly combative. He was a profoundly and self-consciously alienating figure. Furthermore, he positively revelled in his notoriety. The ‘substance’ in Hussey’s case was comparatively inconsequential, his eviction record lagged behind many of his less well-known peers. But with Hussey ‘style’ was as important as ‘substance’. Where wholesale clearances were financially impractical, the optics of house-burning at the few ejectments that did take place assumed additional importance. While it attracted widespread excoriation, burning the cottage of an evicted farmer acted as a powerful psychological disincentive for tenants to default. Public opprobrium did not concern Hussey, not in 1880 and not in his declining years when he doubled down on his record in his self-serving memoir.

Born in 1824 Hussey had experienced the horrors of the Great Famine (at second hand) and was in his prime as an agent when the First Land War began in earnest in 1879 with the founding of the Irish National Land League. Hussey’s memoir is as opinionated as it is entertaining. It is also utterly myopic and partial, almost beguilingly so. Hussey writes of facing death at the hands of moonlighters with the sort of insouciance of a curmudgeonly Great War British battalion commander describing how he regularly despatched ‘the Hun’ to their eternal reward. Hussey began his career as an agent in County Cork in 1845 as an assistant to his brother-in-law. In his reminiscences he observed that he had ‘thus really embarked on the profession of my life, one which, on the whole, I have most thoroughly and heartily enjoyed’. Never has the phrase ‘on the whole’ been required to work so hard. Shortly after this assertion Hussey pointed out the inherent thanklessness of a life as the landlord’s factotum: ‘Lord Derby received threats that if he did not reduce his rents, his agent would be murdered. He coolly replied: ‘If you think you will intimidate me by shooting my agent you are greatly mistaken’.[5]

Lord Derby could well afford to be so cool in his response. As a landlord he was not required to face a fraction of the physical risks of his agent. Furthermore, as prime minister no one was likely to get close enough to him for an accurate shot, although, admittedly, that had not saved the life of one of his predecessors, Spencer Perceval.

Hussey, however, largely shrugged off the copious ill-will towards him, observing of the ubiquitous threatening letter that, although he had received over 100 of such missives, ‘I’ll die in my bed for all that’.[6] That is what almost happened to him and his entire family when the Hussey household in Edenburn, Ballymacelligott, near Castleisland, Co. Kerry was the subject of a dynamite attack in the early hours of the morning of 6 December 1884. The would-be killers were able to plant the dynamite despite the presence of a permanent three-man RIC guard on the house. The ManchesterGuardian offered a graphic description of the event:

‘A large aperture was made in the wall, which is three feet thick. Several large rents running to the top have been made, and it now presents a most dilapidated appearance. The ground-floor, where the explosion occurred, was used as a larder, and everything in it was smashed to pieces, the glass window-frames and shutters being shivered into atoms. On the three stories above it, the explosion produced a similar effect.’[7]

Hussey’s phlegmatic temperament asserted itself in the minutes after the explosion. His first laconic observation was to his wife, ‘My dear,’ he told her, ‘we can have a quiet night at last, for the scoundrels won’t bother us again before breakfast.’ With that he returned to bed. A couple of days later he received a claim for compensation from a neighbour about half a mile distant. The force of the explosion had knocked some of the plaster off her wall. This had then fallen into a pan full of milk, spoiling it. It was probably the least of his worries.[8]

The dynamiters were prepared to kill up to sixteen people in order to end Hussey’s life, which suggests an extraordinary level of both callousness and determination. It was this attack, blowing away much of the rear of his house, which finally persuaded Hussey that it was time to move to London.

Hussey’s main employer, Lord Kenmare, a Roman Catholic landlord, was relatively popular in Kerry. More than a year after the founding of the Land League, in November 1880, 5,000 of his tenants demonstrated in his favour after he had received a letter threatening his life.[9] However, in September 1880 Hussey succeeded in damaging his employer’s status, while reinforcing his own reputation for ruthlessness, by burning the house of an evicted tenant in what was seen locally as an unnecessarily provocative act. Timothy Harrington’s Kerry Sentinel suggested that Kenmare was ‘playing the second fiddle’ to his single-minded agent.[10] By the outset of the First Land War Hussey was agent to Kenmare’s estate of almost 120,000 acres in Kerry, Cork and Limerick and headed a land agency firm that supervised 88 estates and was responsible for collecting around £250,000 in rent per annum.[11] This placed him at the top of the Kerry ribbonmen’s ‘most wanted’ list. Although claiming in his memoir to have been personally responsible for the eviction of only ten tenants over a six-year period from 1879, Hussey’s life was under permanent threat. He admitted that: ‘I never travelled without a revolver, and occasionally was accompanied by a Winchester rifle. I used to place my revolver as regularly beside my fork on the dinner-table, either in my own or in anybody else’s house, as I spread my napkin on my knee.’

Hussey also took the precaution of gifting his daughter a revolver. She slept with this under her pillow and would have been well capable of using it had the need arisen as, during the Land War in the Hussey household, Sunday afternoons were reserved for weapons training and target practice. The agent proudly laid claim to the nickname ‘Woodcock’— so christened by the editor of the Daily Telegraph—on the basis that ‘he was never hit, though often shot at’. Hussey claimed, that even living in London, he was still unsafe, although, he added, ‘if a man shoots me in London he’ll be hung, and every Irish scoundrel is careful of his own neck’. [12]

Hussey’s memoir is interesting in its assessment of the composition of the leadership of the Land League (‘The Land League agitation generally originated with the publicans, small shopkeepers, and bankrupt farmers, rather than with the actual land occupiers’) and his observation that of the six Poor Law districts in Kerry, the most violent agitation took place in the wealthiest (Tralee) and in the most prosperous part of the Tralee Poor Law district, Castleisland (‘which shows that poverty was not the cause’).

Hussey, in ‘there but for the grace of God’ mode, also discusses the murder of the prominent Kerry landlord Arthur E. Herbert. This killing took place near Castleisland in March 1882. The picture Hussey paints of the murder victim is less than flattering.

He was a turbulent, headstrong man, brave to rashness and foolhardiness, and too fond of proclaiming his contempt for the people by whom he was surrounded. As a magistrate, sitting at Brosna Petty Sessions, he expressed his regret that he was not in command of a force when a riot occurred in that village, when he would have ‘skivered the people with buckshot’.

In describing the death of Herbert, Hussey must have been well aware, that, in different circumstances, he might well have shared the deceased landlord’s fate. He certainly did not lack for potential assassins. Like Hussey, Herbert never travelled abroad without a revolver in his pocket. On the day of the fatal ambush in which he died, he even had an armed guard for the first mile of his journey between Castleisland and his home in nearby Killeentierna House where he lived with his eighty-year-old mother. It was after the RIC constable turned back home for Castleisland that Herbert was attacked and killed. The killers made certain of their quarry as ‘The body was almost riddled with shot and bullets’.[13]

A piece of contemporary doggerel offers some indication of the esteem in which Herbert was held by his tenants.

A for poor Arthur who thought he was smart,

B for the bullet that went through his heart;

It goes on …

G for the groan he made when he fell,

H for the hurry he showed going to hell,

I for the Irish who will laugh at the sport.[14]

When it came to tenant marriage Hussey was not as oppressive as his fellow Kerry agent, William Steuart Trench—who insisted on being approached for permission by tenants who wished to marry. Hussey’s memoir also offers a revealing insight into one of the consequences of the end of the practice of subdivision. Although marriage patterns changed post-Famine—with men who were no longer entitled to a share of their father’s farm tending to postpone connubial bliss until they could support a wife and children by some other means—family numbers still remained relatively high. Something had to be done for the sons who were not going to inherit. Hussey described how, in this context, the dowry acquired an even greater importance than in pre-Famine days. The marriage prospects of the son who was due to inherit (not necessarily the eldest) became of vital importance and interest to the rest of the family. In many cases the dowry he received before his nuptials would not accrue to himself but to the disinherited members of the clan, in compensation for their bad fortune.

Hence, if the eldest son were to marry the Venus de Medici with ten pounds less dowry than he could get with the ugliest wall-eyed female in the neighbourhood, he would be considered as an enemy to all his family. A tenant of a neighbour of mine actually got married to a woman without a penny, a thing unparalleled in my experience in Kerry, and his sister presently came to my wife for some assistance.

My wife asked her: ‘Why does not your brother support you?’ And she was answered: ‘How could he support any one after bringing an empty woman to the house?’

To marry ‘an empty woman’ was to commit a crime of the first water. Another tenant of Hussey’s approached him after the death of his (the tenant’s) father, and sought to have his name inserted in the rent book as his father had left him the farm and its stock in his will.

‘What’s to become of your brother and sister?’ says I. ‘They are to get whatever I draw,’ says he. ‘That means whatever you get with your wife?’ ‘That is so.’ ‘Well, suppose you marry a girl worth only twenty pounds, what would happen then?’

‘That would not do at all,’ very gravely. ‘Is there no limit put on the worth of your wife?’ ‘Oh,’ says he, ‘I was valued at one hundred and sixty pounds.’ I found out afterwards he had one hundred and seventy with his wife.[15]

While it is easy to abhor the supercilious arrogance that pervades Hussey’s memoir it is hard not to admire his mordant sense of humour. For example, when asked by the Earl of Lansdowne’s agent, J.Townsend Trench (son and successor of that other agent/memoirist, W.S. Trench, writer of Realities of Irish Life ), ‘How is it, Hussey, that you have not got shot long ago?’ Hussey responded sardonically, ‘I have warned them that if they shoot me, you will be their agent’.[16]

Samuel Murray Hussey, described in his Times obituary as ‘one of the best-known land agents in the United Kingdom’, was as good as his word. He did succeed in dying in his bed—without the assistance of dynamite—at Aghadoe House near Killarney in 1913, nine years after the publication of his self-serving, often thought-provoking, and always highly diverting memoir.

[1] S. M. Hussey, The Reminiscences of an Irish Land Agent (London, 1904), 210

[2] Hussey, Reminiscences, 131.

[3] Donnacha Seán Lucey, Land and popular politics in County Kerry, 1872–86 (PhD thesis, Maynooth University, 2007), 75

[4] Hussey, Reminiscences, 190

[5] Hussey, Reminiscences, 40.

[6] Hussey, Reminiscences, 61.

[7] Manchester Guardian, 7 December 1884.

[8] Hussey, Reminiscences, 240-242.

[9] Kerry Sentinel, 16 November 1880.

[10] Kerry Sentinel, 1 October 1880.

[11] Dictionary of Irish Biography, Vol 4, 860.

[12] Hussey, Reminiscences, 67, 255, 130-131.

[13] Hussey, Reminiscences, 208, 214, 226, 227.

[14] http://www.odonohoearchive.com/castleisland-and-the-herbert-family/ – Accessed 22 March 2022.

[15] Hussey, Reminiscences, 228, 143-44.

[16] L. Perry Curtis Jr. The Depiction of Eviction in Ireland 1845-1910 (Dublin, 2011), 176.

You must be logged in to post a comment.