There is probably no such word as ‘effigised’ but in Ireland there really should be. Then when it came to ‘the burning of an improvised model of a reviled political figure which is constructed in order to be damaged or destroyed as a protest’ – the dictionary definition of this popular pastime— we could say that they had been ‘effigised’. Think of how useful it would be in Northern Ireland when the umpteenth effigy of Robert Lundy is burned by Apprentice Boys who are neither apprentices nor really have any legitimate claim to the title ‘boys’.

Aside from Lundy, who was actually a Scottish Protestant who seemed peculiarly anxious to hand over the city of Derry to the forces of the Catholic King James in 1689, who is the most effigised figure in modern Irish history? Someone you’ve probably never heard of and who hasn’t been burned in effigy for more than a hundred years now, William Keogh. But in his day he suffered many a roasting.

Keogh, who in the course of a relatively short life left hardly a principle unbetrayed, was born in Galway in 1817. His mother was a ffrench, from one of those Anglo-Irish families who added a superfluous ‘f’ to the beginning of their names, presumably to avoid being mistaken for a garlic-eating, beret wearing, consonant-dropping inhabitant of the country immediately to the south-east of England on the far side of the Channel.

Keogh was a gifted youth who, despite studying science at Trinity College, went on to make a small fortune as a barrister, becoming a Queen’s Counsel at the age of thirty-two. In caricatures of the man he looks a little like John Redmond but is remembered even less fondly than the leader of the Irish Parliamentary party in the early 1900s. He was, by all accounts, witty, cultured, a highly impressive speaker and excellent company. He was also self-serving, irascible, insensitive and prone to making unpopular decisions in his own political life and later from the Bench.

In 1847 he became MP for Athlone and campaigned against legislation that would have made it illegal for anyone other than a Church of Ireland bishop to hold an ecclesiastical title. He, and his fellow Catholic Irish MPs of the period, became known, as a result of their campaign, as ‘The Pope’s Brass Band’. Keogh also sided with the Tenant League, which fought for the rights of Irish tenant farmers in the 1850s. So far, so popular. Where did it all go wrong?

Keogh’s problems—at least in terms of his legacy—began when he agreed, in 1852, to be bound by a pledge taken by forty Irish MPs not to accept political office but instead to exploit the possibility of holding the balance of power in the House of Commons. However, Keogh, and the equally reviled John Sadleir, quickly jumped ship and accepted plum jobs in the administration of Lord Abrdeen. Keogh became Solicitor General for Ireland, and later Attorney General. He must have wondered, at times, was it worth it. His name, and that of Sadleir, became a by-word for political treachery.

It only got worse when he became a judge in 1855. He was one of the grumpiest justices who ever sat on the Irish bench. His spectacular quarrels with barristers became legendary. The savage sentences imposed on the rather hapless Fenian prisoners who came before him in 1865 added to his lustre as ‘one of the monsters of mankind’, to quote a description of him on the memorial in Tipperary to two brothers he sent to the gallows for murdering a land agent.

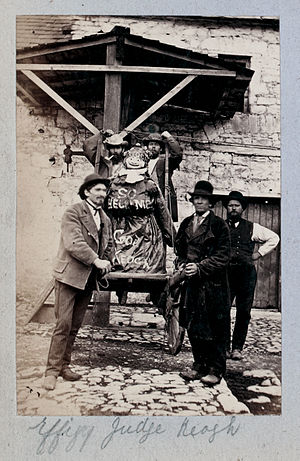

In 1872 in a judgment unseating the victorious candidate in the Galway constituency election he formally handed in his tuba and resigned his membership of the Pope’s Brass band when he lacerated the Roman Catholic clergy and hierarchy from the bench for their interference in the campaign, in a legal decision that took nine hours to read. That was when the effigising began in earnest. He certainly hasn’t been burnt as often as Lundy but he probably holds the Irish record for most effigising in his own lifetime.

As time went on Keogh’s behaviour became more erratic. He was described as ‘eccentric’ a term used to cover wealthy and prominent citizens who are actually stark raving mad. Things came to a head the month before his death in 1878 when he attacked his valet with a razor – one of the old-fashioned ones, not the modern safety type. Jeeves would have resigned on the spot and left Bertie Wooster to his own devices. At least Keogh didn’t end up like Sadleir, who committed suicide after the collapse of his Tipperary Bank in 1856.

So bad was Keogh’s reputation that well into the twentieth century, when offered a seat on the Supreme Court by Eamon de Valera, the former Taoiseach, John A. Costello politely declined, citing as his reason a fervent desire not to stand comparison with the place-seeking Justice Keogh.

William Keogh, barrister, politician and popular effigy was born two hundred and one years ago, on this day.

You must be logged in to post a comment.