Land Acts

A variety of remedial land legislation was introduced in the 19th century, mostly in the last three decades, initially by William E. Gladstone in 1870 and 1881 and later by the Tory government of Lord Salisbury (and his nephews Arthur and Gerald Balfour) in 1887 and the 1890s.

Land Commission

Established in 1881 after the passage of the second Gladstone Land Act, its role went from the arbitration of rents between tenant and landlord, to direct involvement in the land purchase process when it acquired the power to buy estates and re-distribute the land to tenants who were offered loans to enable the purchases. It was re-constituted by the Irish Free State government in 1923, continued the work of land re-distribution until the 1980s, and was dissolved in 1999.

Land Courts

Established by the 1881 Land Act as an arbitrator between tenant and landlord whereby a tenant could apply to the court for a reduction in rent and the decision of the Land Court would be binding on both parties. Initial scepticism about the body gave way to a sudden wave of enthusiasm among tenant farmers when its early decisions reduced rents by an average of 15-20%.

Land League, the

From its origins in Mayo in 1879, the Irish National Land League quickly developed, under the leadership of agrarian activists like Michael Davitt and Patrick Egan, and the presidency of Charles Stewart Parnell, into a vibrant and cohesive national pressure group intent on achieving ‘tenant right’ as well as a reduction of rent and an end to evictions. With agrarian crime levels rising in 1881 the organisation was banned in October of that year and most of its leadership arrested. Their release followed the conclusion of the unofficial ‘Kilmainham Treaty’ (qv)

Ladies Land League, the

Established by Parnell’s sisters Fanny and Anna in 1880 with the latter as the primary motivating force, the Ladies Land League (LLL) came into its own in October 1881 after the Liberal government proscribed the Land League. Anna Parnell’s organisation essentially took over the functions of its ‘brother’ organisation and did so with great efficiency and tenacity. Anna Parnell, who was far more radical than her brother Charles, and the rest of the LLL became surplus to requirements after the conclusion of the so-called ‘Kilmainham Treaty’ and the release from jail in May 1882 of her brother and the Land League leadership cadre. The LLL, because of its inherent agrarian radicalism, also became a political embarrassment to a Parnell whose focus had now shifted to the issue of Home Rule.

Anna Parnell

Land purchase

The transfer of land from landlord to tenant. A small element was contained in the Church Disestablishment Act of 1869 and Gladstone’s 1870 Land Act (‘The Bright Clause’). The Ashbourne Act of 1885 offered terms to landlord and tenant to encourage the process, but this was only marginally successful. The Conservative party chief secretary Arthur Balfour made another attempt in 1891 legislation but it was not until the Wyndham Act of 1903 and its subsequent amendment by Liberal chief secretary Augustine Birrell in 1909 that generous government funding led to the sale by landlords, and the subsidised purchase by tenants, on a vast scale.

Land War, the

A campaign against excessive rents and evictions that began in Mayo in 1879. While the Land League was the public face of tenant opposition to landlord exactions during a period of worldwide economic depression, in the background secret agrarian ‘ribbon’ societies also played a significant role in forcing the passage of the 1881 Land Act and bringing William E. Gladstone to the negotiating table in the formulation of the so-called ‘Kilmainham Treaty’ (qv) which effectively brought the ‘War’ to an end.

Landed Estates Court

The 1858 successor to the Encumbered Estates Court (qv) which took over the sale of the estates of bankrupt landlords.

Land grabbers

The undesirable epithet applied to tenant-farmers who took up land from which the prior tenant had been evicted and, from 1919-23 to ‘squatters’ engaged in the illicit seizure of land. See also ‘grabbers’.

Latitat

A writ or summons generally issued on the assumption that the object of the summons is in hiding.

Middlemen

Someone who rented land from a landlord and then sub-let to others. Some middlemen were wealthy minor gentry, some were businessmen or professionals, others were farmers who worked their own land as well as subletting. On some estates there were ‘layers’ of middlemen, with, perhaps, a single middleman sub-letting to other members of a species that had become seriously endangered by the end of the 19th century and was close to extinction a hundred years later..

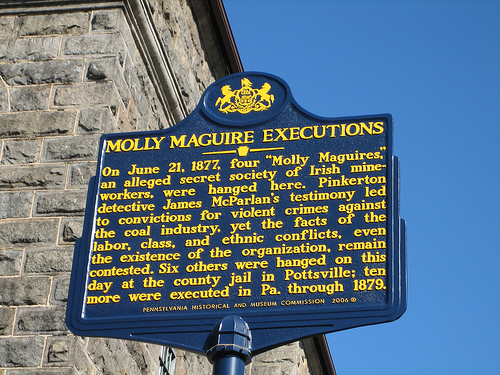

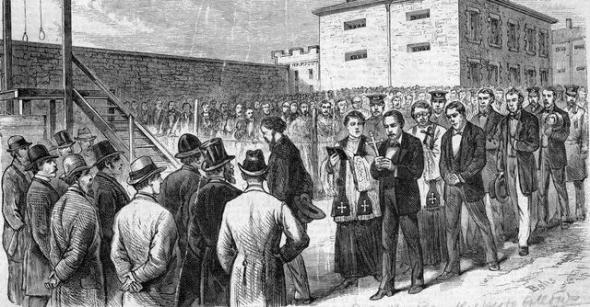

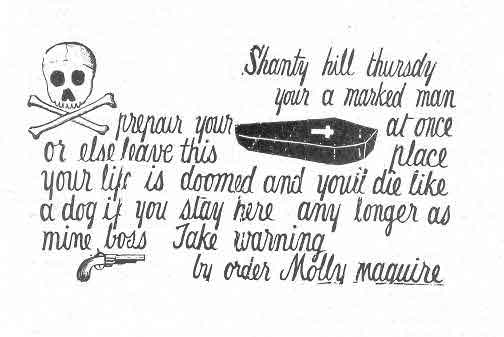

Molly Maguires

A secret society suspected of the murder of Roscommon landlord, Denis Mahon. The term was later applied to the fraternal Ancient Order of Hibernians (a Roman Catholic counterpart of the Orange Order) and to a secret society based in the anthracite fields of the US state of Pennsylvania.

Major Denis Mahon

Newtownbarry

Today known as Bunclody, it was the scene in June 1831 of an affray that led to the killing of at least eighteen anti-tithe protestors by members of the Yeomanry militia. It was also the last time a Yeomanry company was used in a policing operation.

Oakboys (see Hearts of Oak)

Ordnance Survey

Beginning in 1825, and employing, among others, future Irish under-secretaries Thomas Drummond and Thomas Larcom, the Ordnance Survey mapped the country thoroughly for the first time since the Down Survey.

Pastorini

The 18th century millenarian prophecies of Bishop Charles Walmsley (‘Pastorini’ was his pen-name) which predicted the demise of Protestantism in the 1820s. Walmsley’s writings influenced many of those who participated in the Rockite insurgency of the 1820s.

Bishop Charles Walmsley

Pound

An area of confinement where distrained livestock were kept prior to being auctioned. Also a unit of currency rarely if ever seen by Irish landless labourers or cottiers.

Process server

An agent employed to serve eviction notices on tenants in arrears. As well liked and respected as a serious case of leprosy.

Property Defence Association

A largely unionist landlord organisation established during the Land War to protect the interests of landlords against the rival tenants combination, the Land League.

Ranch War, the

The outcome, from 1906-09, of a movement composed largely of small farmers and landless labourers, and led by Irish Parliamentary Party politicians, such as Laurence Ginnell, who campaigned against the move from tillage to pasture and the consequent reduction in the number of farms for purchase or rent. Often characterised by the illicit activity of cattle ‘driving’ (qv)

Laurence Ginnell MP

Replevy

To re-deliver distrained goods to their original owner after receiving financial guarantees. In Castle Rackrent Maria Edgeworth writes of Sir Murtagh, ‘he was always … replevying and replevying.’

Ribbonmen, the

The name by which members of secret agrarian societies came to be known by the middle of the 19th century, largely replacing the term ‘Whiteboy’. However, the Ribbonmen were, initially at least, more politicised, and emerged from the ‘Defender’ tradition in Ulster. Ribbonism also had a foothold in Dublin, unlike any of its purely rural predecessors.

Rockites, the

A well-coordinated agrarian secret society, often driven by anti-Protestant millenarianism (see ‘Pastorini), which posed a major threat to the authorities in Munster in the 1820s. Named after the mythical ‘Captain Rock’ (qv) who ‘signed’ many of the threatening letters issued to agents, landlords and non-compliant tenants.

‘The Installation of Captain Rock’, Daniel Maclise 1834

Rundale

A co-operative tenurial system based on a clachán (qv) or small community in which land was held collectively and its distribution settled by local agreement.

Rightboys, the

A largely Munster-based agrarian secret organisation of the 1780s whose main grievance was the obligation to pay tithes. The name derives from their allegiance to the mythical ‘Captain Right’.

Shanavests, the

The rivals of the Caravat (qv) secret society in a class-based conflict in Munster and south Leinster from 1806-11. The Shanavests were prosperous farmers who combined to resist the antagonism of small farmers and labourers.

Sive (Sieve) Oultagh

The mythical guiding light of the Whiteboys whose signature was often appended to threatening letters from the organisation. Other exotic names used in this context included Joanna, Shevane Meskill and the more masculine Lightfoot, Slasher, Cropper, Echo, Fearnot and Burnstack.

Steelboys, the (see Hearts of Steel)

Terry Alts, the

A secret society that emerged in County Clare in the late 1820s, post-Rockite and pre-Tithe War and was responsible for a number of murders, the most celebrated being the killing of Captain William Blood, land agent of Lord Stradbrooke in 1831.

Three Fs

‘Fair rent, Free sale. Fixity of tenure’. An ongoing slogan since the days of the Tenant League. Finally given legal status in Gladstone’s 1881 Land Act.

Tithes

A form of taxation payable to the clergy of the Established Church and a frequent bone of contention, especially with members of the Roman Catholic and Presbyterian faiths. The nature of the tax varied from region to region and, for a long time, livestock farmers were exempted from the levy. The so-called ‘Tithe War’ of the 1830s led to the Tithe Rentcharge Act of 1838 which ended the anti-tithe agitation.

Tithe proctor

An agent who established crop valuations and collected tithe contributions on behalf of a Church of Ireland rector for a commission of around 10%. As welcome as gout.

A visit from the tithe proctor

Tithe farmer

Someone who reached agreement with a local rector to take on the collection of tithes on payment of an agreed sum to the clergyman. How he then made a profit was dependent on how much he could extract from those in the local parish liable for the tax. As popular as syphilis.

Tithe War

A conflict that spawned the effective, but relatively uncoordinated movement which led to the transfer of direct responsibility for the payment of tithes from tenants to landlords. The ‘war’ began in Kilkenny in 1830 and included two notable atrocities, at Newtownbarry, Co. Wexford (qv) in June 1831 where yeomanry killed fourteen protestors and at Carrigshock, Co. Kilkenny (qv) in December 1831 where a process server and twelve policemen were killed.

Ulster Custom

The right of a tenant to be compensated for improvements when vacating land (either voluntarily, or as a result of eviction proceedings) or to sell his ‘interest’ in the land. Also known as ‘tenant right’ it was supposed to exist throughout Ulster, although this was often disputed by landlords, as the incoming tenant was expected to pay for the interest or fund the compensation and this tended to reduce the potential rent.

Whiteboys.

An agrarian secret society that originated in Tipperary in 1761 in opposition to the enclosures of common land. The movement then spread into neighbouring counties with an expanded agenda. Named for the white shirts worn over workday clothing. The movement died away by 1765 but re-emerged in 1769 in opposition to high rents, evictions and excessive levels of tithe payments. The term ‘Whiteboy’ continued to be used in the early 19th century as an umbrella term for violent agrarian activity, until it was gradually supplanted by the term ‘Ribbonism’. The 18th century legislation against agrarian crime passed in 1766, 1776 and 1787 became known as the ‘Whiteboy Acts’.

Whiteboy activity

Whitefeet

An offshoot of the Whiteboys, in that this was a secret agrarian society which emerged in the Carlow-Kilenny area in the 1830s in imitation of the 18th century Whiteboys.

You must be logged in to post a comment.